Roasted Aubergine Salad and Istanbul’s Other Vegan Tastes

Glancing through glossy pages of travel magazines or holiday sections of Sunday supplements, or flicking through popular culture, one might be forgiven for assuming Istanbul’s culinary culture is predominantly if not exclusively carnivorous. Magazines, guide books, online culinary blogs, and amateur or professional travelogues’ social media accounts are swarming with vivid photos of sizzling meat, meticulously arranged kebab choreographies, and interminable “Top Grills in Istanbul” lists.

In fact, vegetables – fresh and dry – and greens occupy an at least as central, if not more so, than meat in Istanbul’s cuisine. So much so that, as columnist Leyla Yvonne Ergil points out, “There is a surprisingly wide variety of Turkish staple dishes that are both delicious and decidedly vegan.” This is particularly true for mezzes and as anyone who has ever been to an Istanbul meyhane very well knows, barring a handful of seafood dishes (including the queen of mezzes lakerda) most of the mezzes offered are vegetable, legume, or green-based and are served with either an olive oil/lemon juice dressing or warm tomato sauce.

According to historian and culinary expert Marianna Yerasimos, the Armenian population in Istanbul discovered the use of tahini during lent. In order to avoid ending up with bland dishes, they would cook everything “from soup to flat bread” with tahini.

Even the wide ranging variety of non-meat or fish based mezzes Istanbulites regularly enjoy alone reveals how key a role vegetables play in Istanbul’s culinary culture: black-eyed bean salad, glassworts, papaz mancası (fried aubergines and green peppers in a garlic and tomato sauce), stuffed vine leaves, stonecrops, favetta, haydari (thick yoghurt dish made with plain yoghurt, feta cheese, fresh herbs, and olive oil), tzatziki, tirosalata, wild radish leaves salad, baba ghanoush, and the list goes on.

The Land of Plenty

Like every single aspect of Istanbul’s culinary culture, the frequent use of a diversity of vegetables in cooking also dates back to Byzantine times. Although numerous men of classical medicine (wrongly, we might add) warned the public and rulers alike that excessive consumption of vegetables and greens would cause lethargy, flatulence, and gloominess, as historian Michael Grünbart has shown, “Fruits, plants, and fresh vegetables played an important part in the Byzantine diet.”

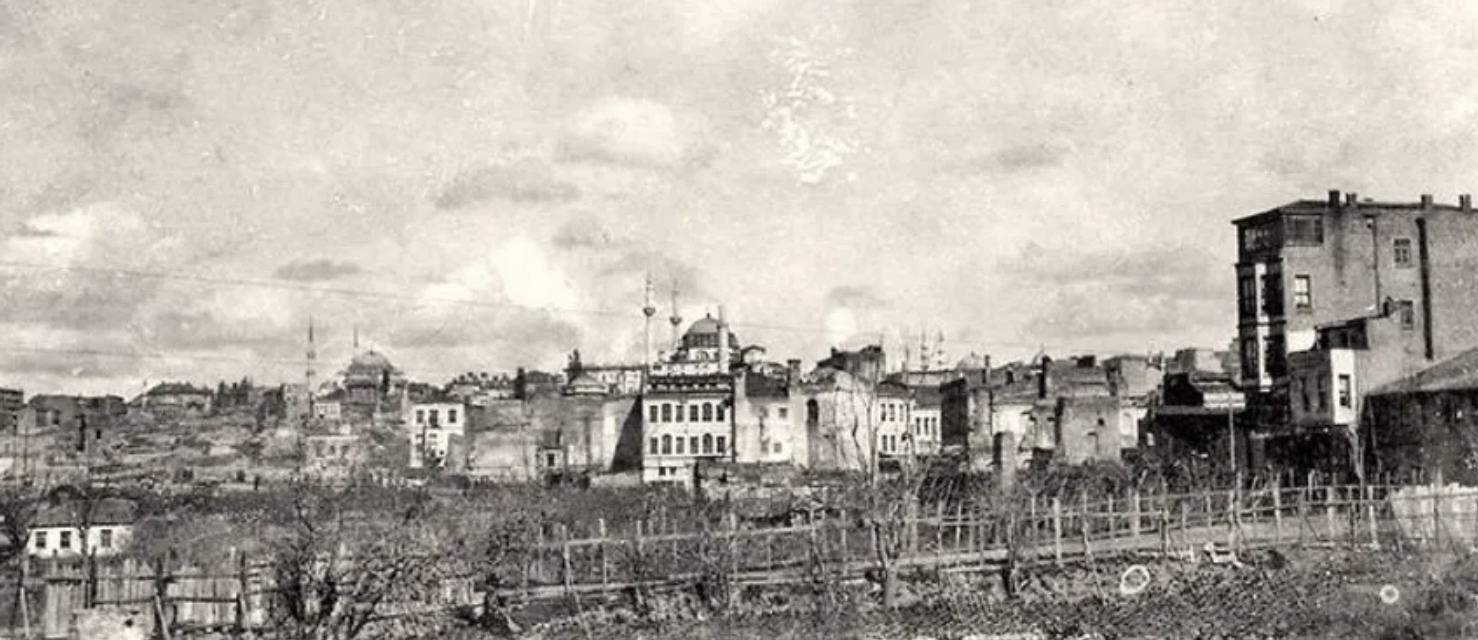

There were two interrelated reasons for this: Vegetables (like greens and fruits) were plenty and cheap (compared to meat at least). Bostans (the city’s market gardens) and gardens inside the city walls and outside, spread across both shores of the Bosporus provisioned Constantinople and Istanbul with fresh vegetables, greens, and fruits from the 5th century onwards. In short, the Byzantine population, especially the lower classes that didn’t necessarily have access to meat, always had plenty of fresh produce to enjoy and experiment with.

Roger Verge: “Gleaming skin; a plum elongated shape: the eggplant is a vegetable you’d want to caress with your eyes and fingers, even if you didn’t know its luscious flavour.”

Things didn’t change with the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453. If anything, the city became more fertile as centuries flew by. The Ottoman rulers rightly considered the bostans’ and gardens’ presence as a means to secure the livelihood of the ever-increasing population in the city and therefore imposed a strict regulatory system, which ensured vegetable and fruits continued to be grown seamlessly for centuries. And, it wasn’t just the large bostans and gardens owned by the Palace; as historians Ebru Bayar and Kate Fleet rightly argue, smaller gardens belonging to individual households were also quite prevalent. Taking advantage of the city’s fertile soil at the time, Istanbulites grew their vegetables and greens of choice, turning the imperial capital into a hub of urban agriculture.

So smoothly did this system function that according to leading Ottoman historian İlber Ortaylı, even during the hardest days of the Great War, when Istanbulites couldn’t get their hands on meat or bread, there was still no shortage of fresh vegetables and greens.

The City’s Favourite Vegetable – or, Fruit?

According to travelogue Evliya Çelebi, by 17th century there were nearly five hundred sebzevatçı (street vendors selling vegetables) registered in the capital. And the produce that these men who carried fresh vegetables, greens, and fruits in large wicker baskets they carried on their shoulders sold the most? Aubergines.

Istanbulites indeed did and continue to love their aubergine. The first Ottoman cookbook, written by Cypriot Mehmet Kamil Pasha and titled Melceü’t-Tabbahin (or, A Refuge for Cooks) lists eleven dishes made with aubergines in the special “vegetable dishes” section, which in total includes twenty-six recipes. A similar trend can be observed in more contemporary cookbooks where aubergines are always in a leading role in vegetable dish sections. And the sheer number of different dishes that can be made using them is mesmerising; aubergine fritters, stuffed aubergines, deep-fried aubergines, skewed aubergines, beğendi (puréed aubergines with lamb), moussaka, roasted aubergine salad, and many others. What is it that makes aubergines such a favourite for Istanbulites?

Before answering that question, a point of clarification is in order: by botanical definition and despite being typically used as a vegetable in cooking, aubergine is in fact a berry. First produced in India and China, it arrived in Istanbul with Byzantines. Indeed, it was unknown to classical cuisine and neither Greeks or Romans had a name for aubergines. On the contrary, there are numerous Arabic and North African names for it, indicating that it was grown throughout the Mediterranean by Arabs and North Africans.

And the reason why Istanbulites have adored it for centuries? Despite being nutritionally low in macro and micronutrient content, the fruit has an exceptional capability to absorb oils and different flavours (of herbs and spices among others) into its flesh through cooking. In a city where the richest of olive oils were available to the population that in turn excelled in cooking with it and which stood at perhaps the most significant spot on the Silk Road and hence on the Spice Trade, aubergine was simply destined to become an indispensable part of the culinary culture..

According to a 2020 SIA Insight study titled Dietary Habits in Turkey, the number of urbanites (living in Istanbul, Ankara, and Izmir – the three biggest cities in the country) that self-identify as vegan is around 80,000. Veganism’s rise particularly in Istanbul is also attested to by the number of vegan associations that currently exist in the city: of the 28 associations in Turkey, 10 are based in Istanbul.

And of course, realising Istanbulites’ penchant for the vegetable-cum-fruit, meyhanes were quick to ensure they would serve the tastiest, most succulent aubergine mezzes to their habitués. Some of the dishes have meyhane frequenters have been enjoying for decades if not centuries include: şakşuka (fried aubuergines, potatoes, and courgettes, served with a garlic tomato sauce); kuru patlıcan dolması (dried aubergines stuffed with spicy pilaf); patlıcan pabucaki (grilled aubergines stuffed with fried onions, peppers, tomatoes, and olive oil and topped with salty feta or mihaliç cheese); and, last but not least, patlıcan ezme (roasted aubergine salad garlic, lemon juice, olive oil, black pepper, and parsley).

Practice Makes Perfect

Members of Eastern Churches have been calling Constantinople and Istanbul a home for centuries now. And, like with other cities where a well-established Christian culture has prevailed, a tradition of Biblical fasting has existed here for millennia. Fasting 40 days for the Christmas Lent, 48 days for the Easter Lent, and 15 days for the Fast of the Dormition (assumption for the catholic church) of the Mother Of God has meant observant Christian Istanbulites have had to spend almost one third of the year without enjoying any meat products, including animal fats, meat broth, or butter. And it is this spiritual discipline that has led them, or even forced them to explore ways to do more with what they were allowed to consume and what they had plenty of: vegetables. For centuries, they’ve experimented with greens, leaves, root vegetables, legume, onions and garlic, herbs and spices, and of course olive oil to be able to enjoy their food even while fasting. And the result? A plethora of vegetable dishes, mezzes made with greens, and vegan food so luscious, so rich that Istanbulites cannot even fathom living without them.