From the Bozahouse to the Bar by way of the Beerhouse

For centuries, two types of boza were available in Ottoman Istanbul: sweet, alcohol-free boza and sour boza, with enough alcoholic content to, at least temporarily, serve as a substitute when wine and rakı were banned. According to Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi, Tatars and gypsies were experts in making sour boza, and the most famous brand in the 17th century was Ayasofya (Hagia Sophia), which had such strong alcoholic content that it was the choice boza of the Janissaries.

Boza Vendor, source: Karakedıbozacisi.com.tr

Although mobile boza sellers roamed the streets of Constantinople, it was mostly in licensed bozahouses that Istanbulites preferred to consume this thick, malt drink primarily because it also gave them an opportunity to socialize with their fellow urbanites and enjoy good food. During the 16th century, it was predominantly upper classes – especially the ulema, men of letters – who frequented these establishments known for their succulent kebabs and fried liver.

Philippe de Champaigne, Portrait of Jean de Thévenot, ca. 1660 (formerly believed to be a portrait of Antoine Galland by Gerbrand van den Eeckhout) Oil on canvas, 59.7 x 43.2 cm, The Huntington Library, inv. 2010.2, source: wikipedia

According to Çelebi, in 17th-century Istanbul, there were 300 licensed bozahouses, of which only 40 exclusively sold the sweet kind. By the time of his writing, bozahouses had also become more inclusive spaces where men from all classes, “the ulema and flour porters,” drank boza together. The popularity of boza, according to French traveler Jean Thévenot, was due to its cheapness. Even establishments, which were licensed to sell only the sweet kind offered their regulars the sour version under the counter, and lower classes, who couldn’t afford wine, imbibed vast amounts of boza – more than enough, by all accounts, to have made Dionysus proud.

Blondish Water with White Foam

By the mid-19th century, sour boza had all but disappeared from Istanbul as a result of two concurrent developments. First, wine and rakı became cheaper and more accessible with the Sultans finally giving up on the idea of banning their consumption. Second, a more delectable and enjoyable fermented malt drink made its way to the capital from Europe at the turn of the century, attracting the city’s youth who longed for a Western lifestyle.

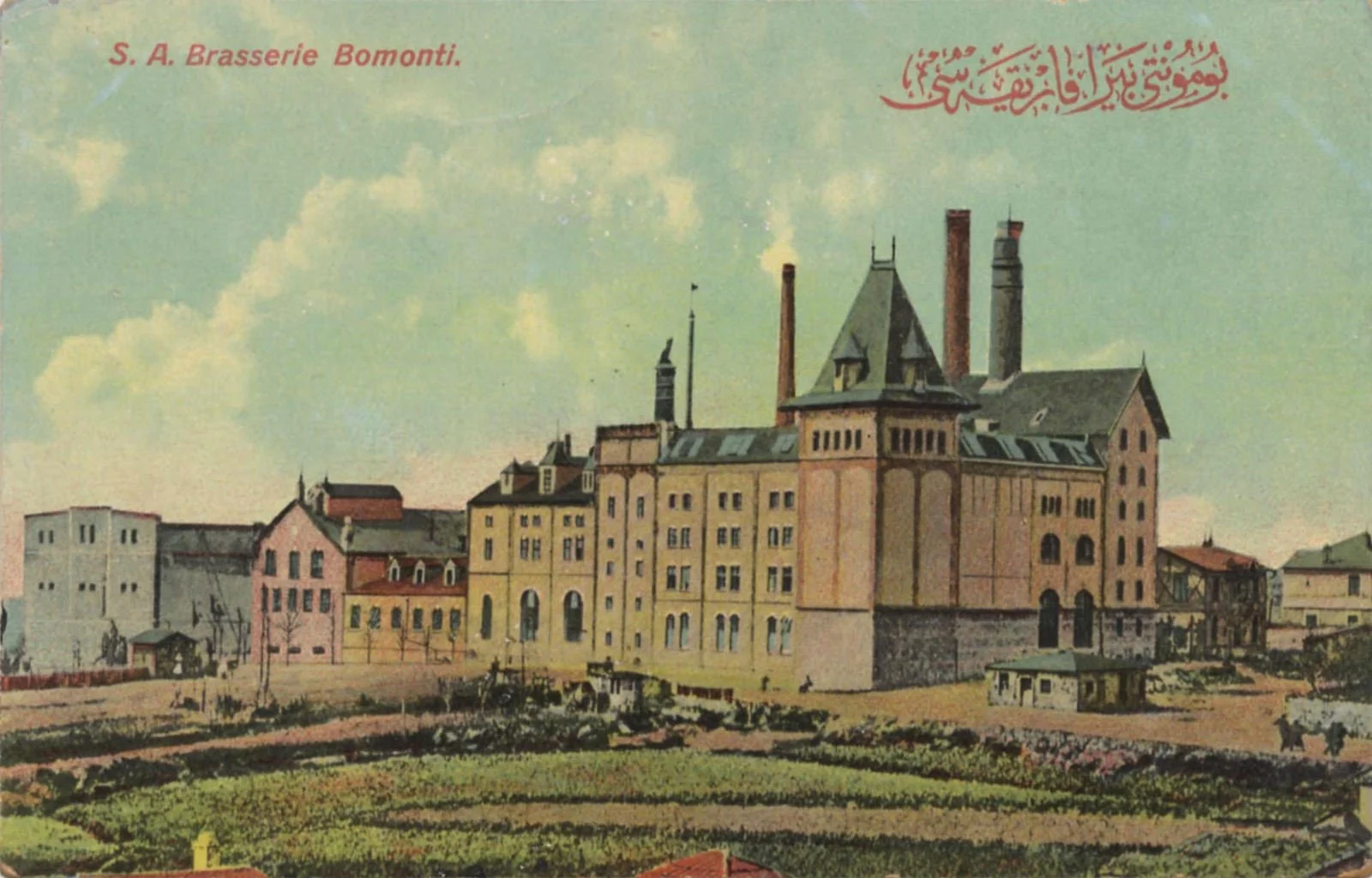

Bomonti Beer Factory, source: Osmanlı'dan Cumhuriyet'e Biraya Dair: Objeler, Belgeler, Fotoğraflar

Most of the beer sold in Istanbul during the early 1800s came from Vienna, Belgrade, and Munich in steamships. But it was only in the second half of the century, with rapid advancements in refrigeration technology and, of course, the invention of pasteurization, that beer’s popularity hiked. So much so that, in 1890, the first beer factory in Istanbul was opened by the Swiss Bomonti brothers, and in 1891, Annuaire oriental du commerce listed more than 40 stores selling beer in the city.

Beerhouse as an Apolitical Space

In 1881, Johannes Winkler, an Austrian man of cloth, spent a couple of weeks in Istanbul on his way back home from Jerusalem. He was delighted to have found plenty of establishments selling beer in the city as he “was finally able to quench his thirst.” Although he bemoaned how expensive beer was in Istanbul, he and his companions visited a different beerhouse every night, turning this into one of the “most memorable fortnights,” of his life.

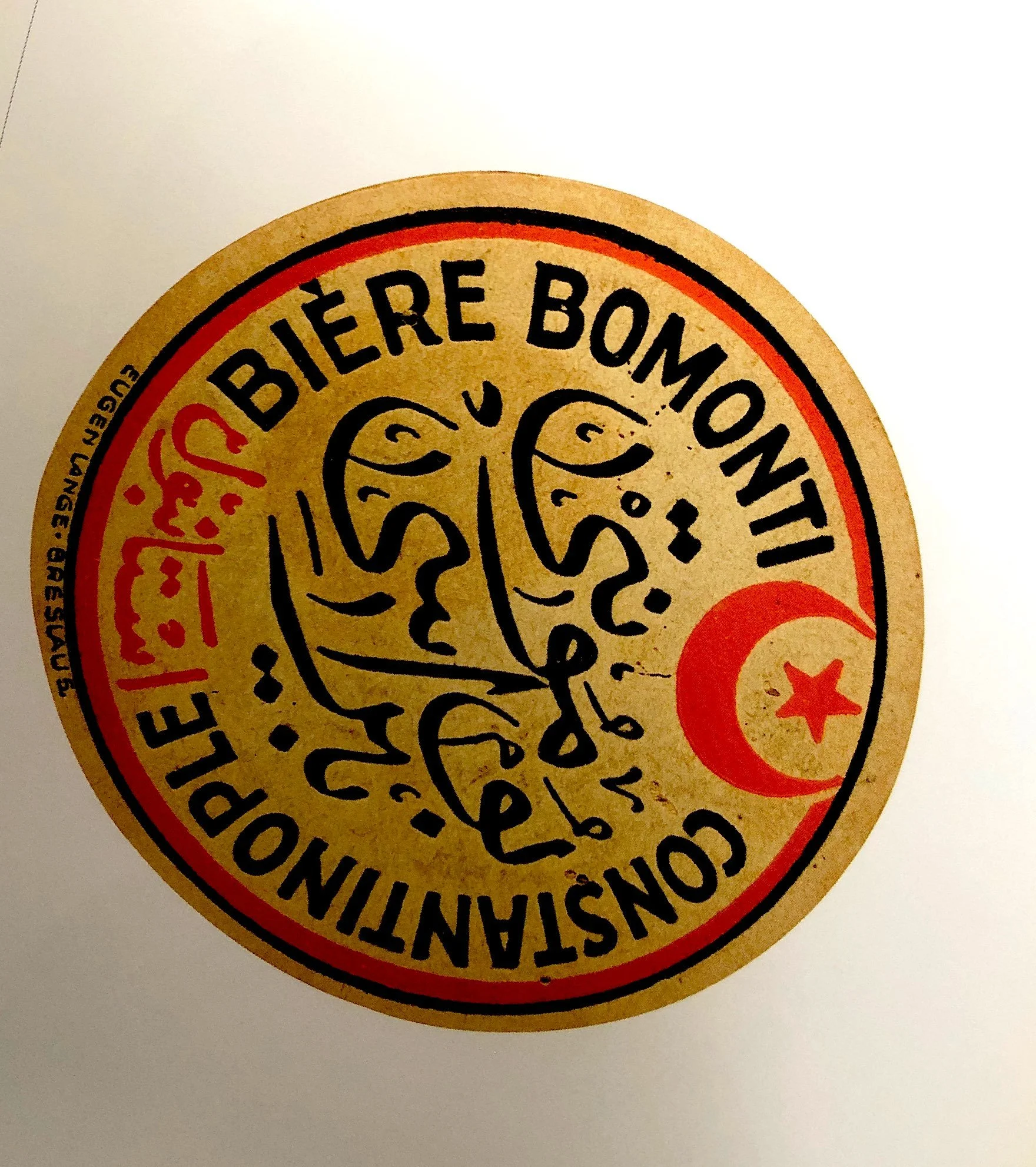

Bomonti Coasters, source: Osmanlı'dan Cumhuriyet'e Biraya Dair: Objeler, Belgeler, Fotoğraflar

The first beerhouse in the city was opened in the early 1840s, right after the proclamation of Tanzimat Reforms, which allowed for more freedoms for Ottomans. The first of these were converted from bozahouses by business-savvy Rum Istanbulites and foreigners – early adapters of a different age. By 1890, more than 30 beerhouses were operating in Istanbul – an astonishingly high number considering that since 1876, on the throne sat Abdülhamid II, a sultan known to fear and loathe his socializing subjects.

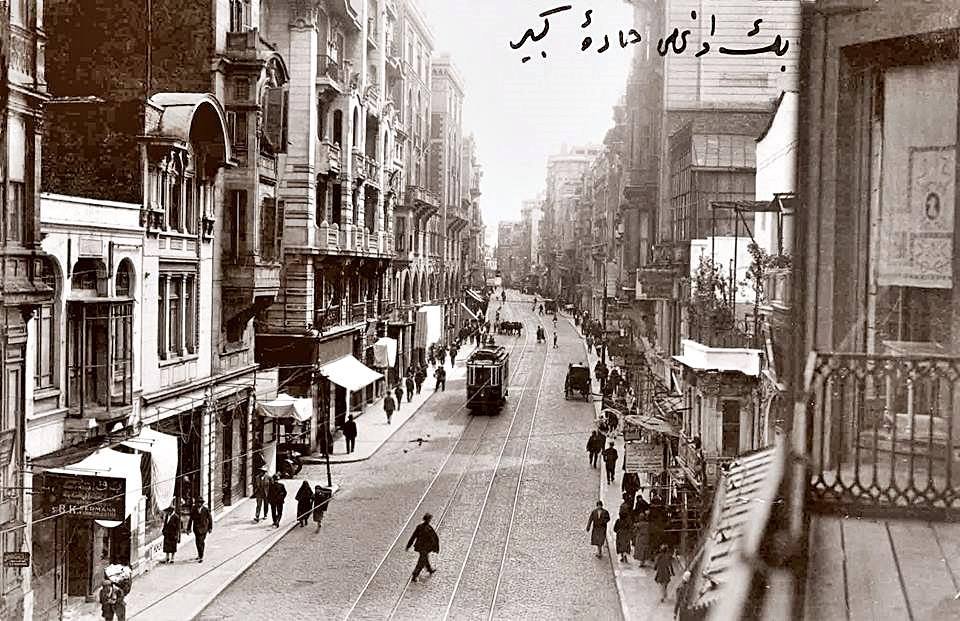

View of Cadde-i Kebir (Istiklal Avenue) from a 1920s London Pub, source: aposto.com

Although the exact date is not known, there is consensus among historians that the first beerhouse opened in Istanbul was Londra Birahanesi, a.k.a. the London Beerhouse. Located on the Grande Rue de Péra, no. 284, the three Rum waiters of the London Beerhouse – Nikoli, Yani, and Ananiyas – all went on to own their own establishments in the following years. An interesting fact about the London Beerhouse was that despite what its name might have indicated, its owner was a German by the name of Bruchs.

Marsilya and Stein Beerhouses, source: Osmanlı'dan Cumhuriyet'e Biraya Dair: Objeler, Belgeler, Fotoğraflar

So, the question was how could the number of beerhouses proliferate under his rule?

Fearing that the young, progressive circles in the capital would revolutionize the rest of the population and dethrone him, the Sultan had set up a vast network of spies reporting on the daily activities of his subjects. The use of “dangerous” words, including but not limited to nihilism, socialism, anarchism, republic, constitution, tyrant, spy, equality, justice, freedom, revolution, and assassination was prohibited and his secret agents would inform on anyone who used any of these words in their daily lives; books including Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables, John Milton’s Paradise Lost, and Émile Zola’s Germinal were banned; and, his spies kept a very close eye on any communal event or activity where groups of Turks came together, such as plays, picnics, and even, team sports, and especially football. So, the question was how could the number of beerhouses proliferate under his rule?

Bosporus Beerhouse, a.k.a. Nikoli’s Place was opened in 1885 in Galata. Frequented almost exclusively by young Ottomans, Levantines, and foreigners, Nikoli’s was the first beerhouse to offer an extensive array of mezzes such as radishes, tuna fish, kalamata olives, gruyere cheese, anchovies, dried mackerels, smoked tongue, fried mussels, and brain salad.

According to chroniclers from his time, the Sultan was unsurprisingly paranoid about the beerhouses during the first few months of his reign. However, his most trusted aides advised him to leave them alone, as they deemed the habitués of beerhouses to consist primarily of apolitical Istanbulites and foreigners, living the lives of the most committed hedonists the world had ever seen. And so, they were not only left untouched but allowed to bloom, and by the end of the century, Istanbul had become home to several famed beerhouses.

Source: maviboncuk.blogspot.com

Opened in the early 1870s on the Grande Rue de Péra, no. 246, Sponeck was renowned for its Italian delicacies and biscuits served München beers. Owned by a Rum named Alataris, Sponek became the first place in Istanbul to screen a moving picture by the Lumiere Brothers on January 16th, 1897.

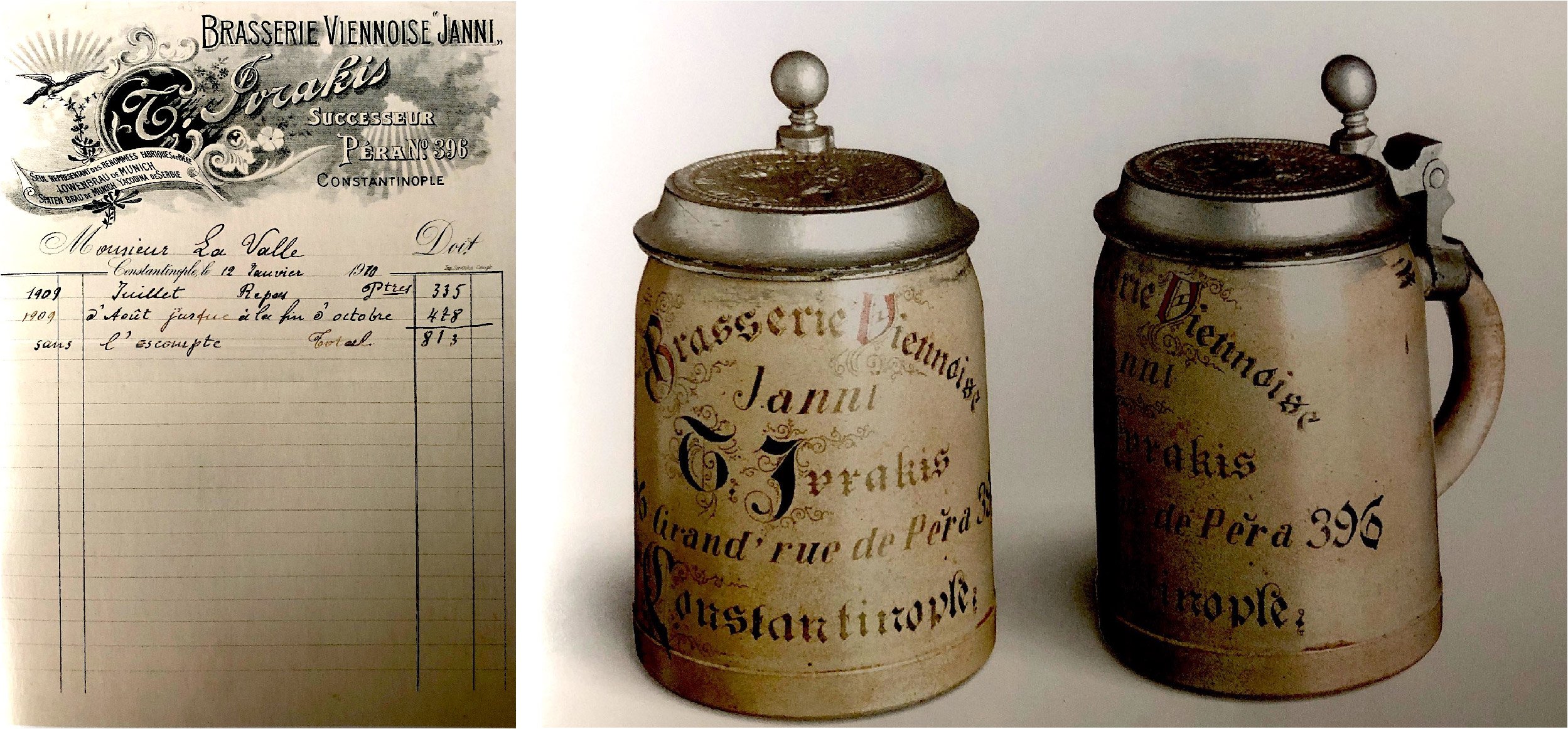

Left: Yanni's Bill, source: Osmanlı'dan Cumhuriyet'e Biraya Dair: Objeler, Belgeler, Fotoğraflar,

Right: Yanni's Steins, source: Osmanlı'dan Cumhuriyet'e Biraya Dair: Objeler, Belgeler, Fotoğrafla

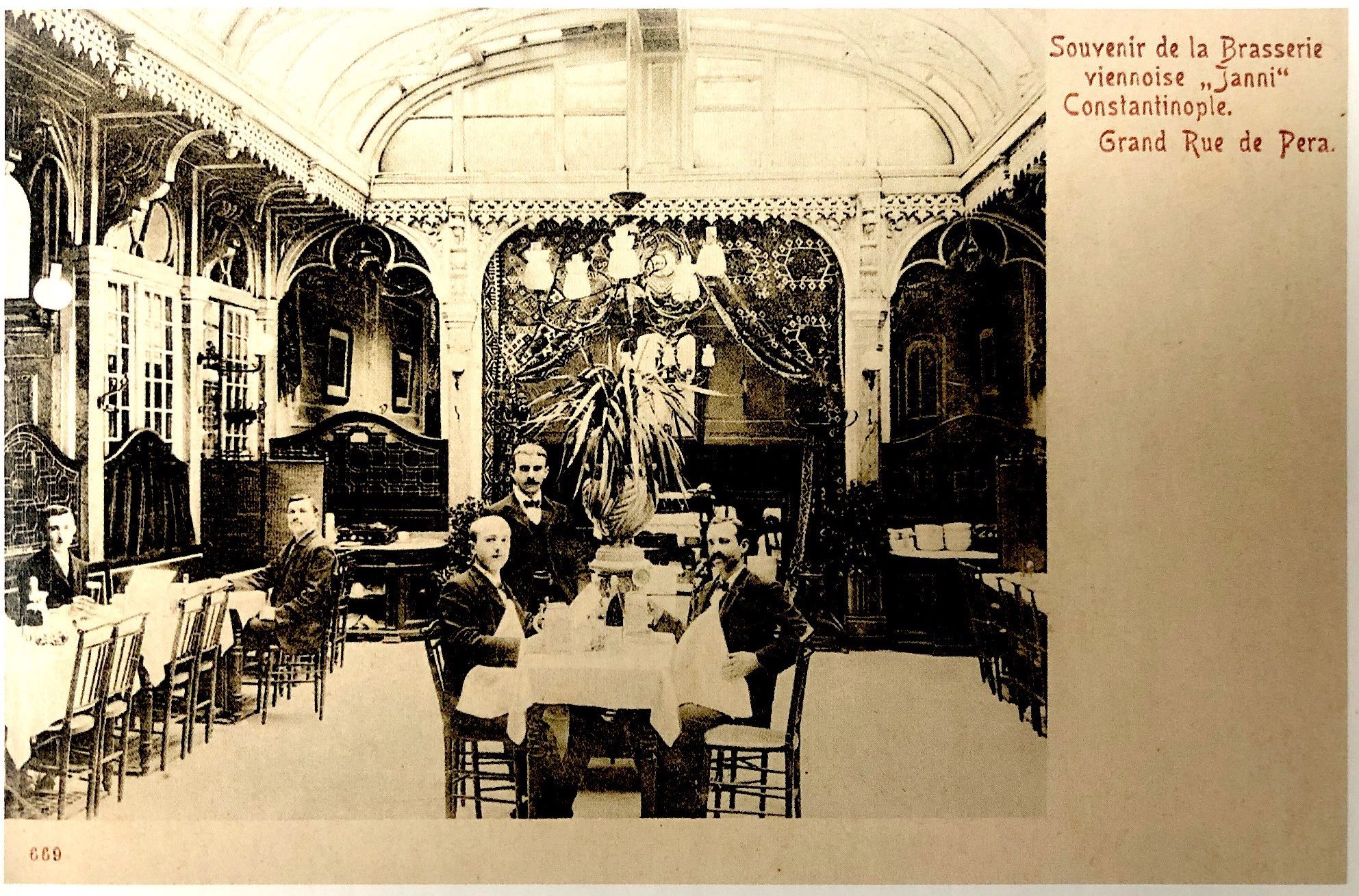

Of all the beerhouses of late-19th century Istanbul, none was as prestigious as the Vienna Beerhouse, better known as Yanni’s. Opened in 1878 by Yanni Cacavopoulos on Gönül Street near the Cité de Syrie in Beyoğlu, in 1890 it moved to the entrance floor and back garden of Kanavaloff Apartment on Grande Rue de Péra, no. 396, right across from the Russian Embassy.

Left: Bomonti Beers, Right: Bomonti Coasters, source: Osmanlı'dan Cumhuriyet'e Biraya Dair: Objeler, Belgeler, Fotoğraflar

Yanni’s served a wide range of beers including Salvatore, Spatten, Drehen, Löwenbräu, and the local Bomonti alongside oysters, Roquefort cheese, green olives, and dried mackerel.

Yanni's Garden, source: Osmanlı'dan Cumhuriyet'e Biraya Dair: Objeler, Belgeler, Fotoğraflar

Yanni's Inside View, source: Osmanlı'dan Cumhuriyet'e Biraya Dair: Objeler, Belgeler, Fotoğraflar

Its regulars were heavy-drinking, cosmopolitan elite who enjoyed playing backgammon and bridge or diving into the European newspapers offered free of charge to all customers. Yanni allowed almond and pistachio sellers to do business inside as he believed that the more of these his customers ate, the thirstier they’d get and the more beers he’d sell. In 1895, Taxiarchis Ivrakis bought the premises but very cleverly kept its name, and Yanni’s continued to be the urban elite’s first-choice beerhouse until the outbreak of the First World War.

Yanni's Street View, source: Osmanlı'dan Cumhuriyet'e Biraya Dair: Objeler, Belgeler, Fotoğraflar

Strasbourg Beerhouse was opened in 1883 by a Frenchman called Bauczek. In 1898, Yanni Palicronis bought it, and the beerhouse came to be known as Yanni’s II. Located on Grande Rue de Péra, no. 426, and serving mostly imported beer from Germany, Strasbourg was a favorite meeting spot for French journalists and teachers from Lycée de Galatasaray.

Brasserie de Caucase played a prominent role in Istanbul’s beer scene, albeit under different names, for almost a century.

Brasserie Kohout, source: Osmanlı'dan Cumhuriyet'e Biraya Dair: Objeler, Belgeler, Fotoğraflar

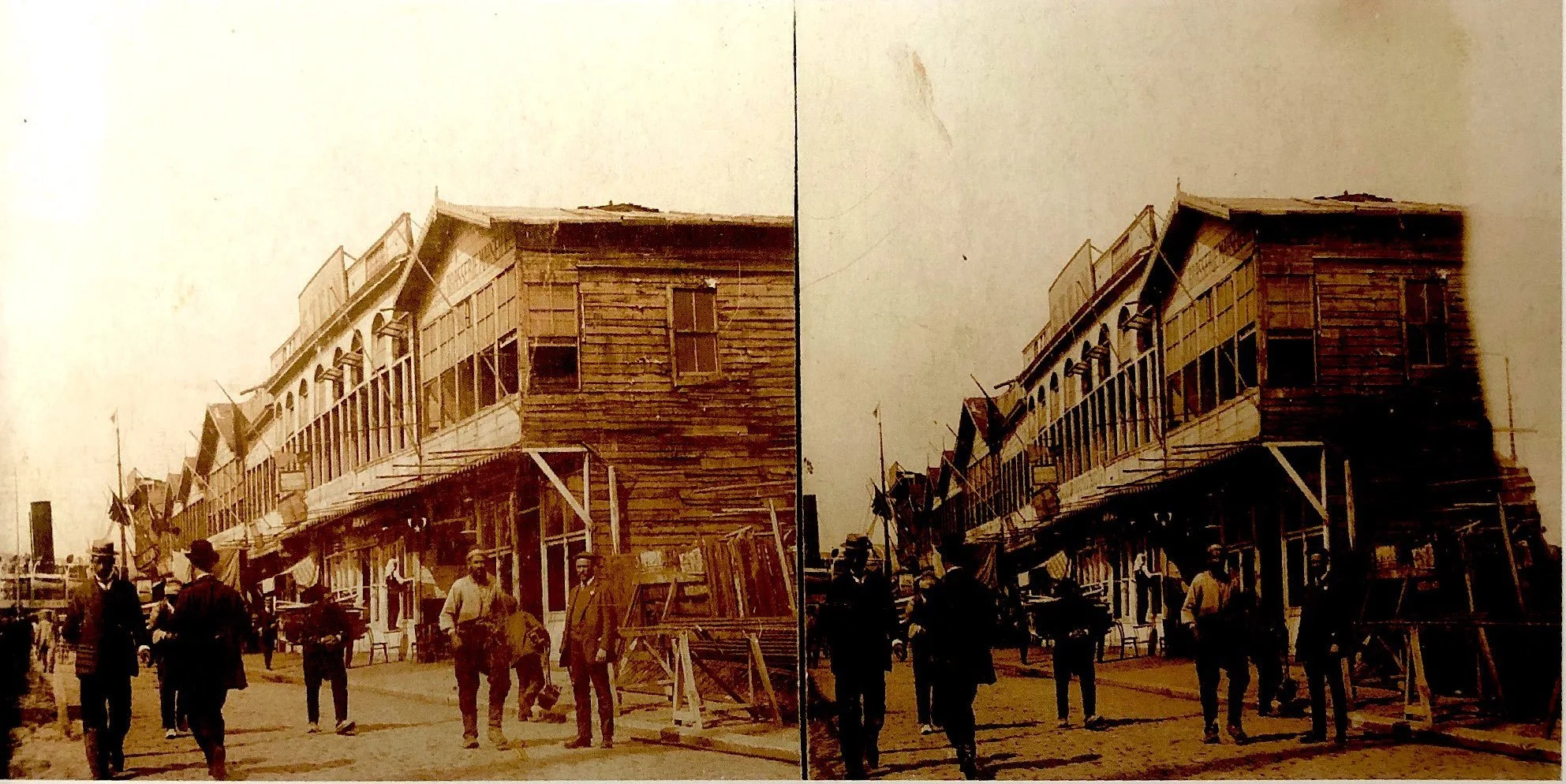

Not all of the late-19th-century beerhouses were in Pera or Galata. Located in Sirkeci’s Bab-ı Ali Street, no. 28, Brasserie de Caucase played a prominent role in Istanbul’s beer scene, albeit under different names, for almost a century. Its Rum owner, who opened the beerhouse in 1860, named it Caucasian thinking that it would attract the rising number of emigres from the region. He was right, and Kafkasya Birahanesi, as it was known in Turkish, became one of the most popular spots for beer lovers in Istanbul. However, it was the opening of Sirkeci Train Station, the terminus for the Orient Express, that caused a real surge in customer numbers. Until being destroyed by a fire in 1945, the beerhouse continued to attract Istanbulites, especially poets and journalists. Amidst all the owner changes and different names, one thing remained constant at the Brasserie: waiter Adem Çulfas. Born in 1878 in Gümüşhane, Çulfas, a.k.a. meister, started to work at İştayn Bruh (the Turkish spelling for Steinbräu) as the beerhouse was called in 1905 and remained as its head waiter until the building’s demise in 1945.

Beerhouse token, source: Osmanlı'dan Cumhuriyet'e Biraya Dair: Objeler, Belgeler, Fotoğraflar

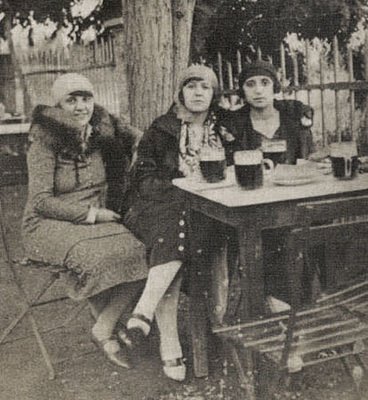

Ladies enjoying the beer in the beer garden, c. 1930 and 1950, source: levantineheritage.com

Kizizana Beerhouse was the first in Istanbul to offer a women-only salon within the premises. It also prided itself in being the first automatic beerhouse of the Orient as there was a beer dispenser that worked with special tokens in the aforementioned salon.

Bomonti Beer garden, source: levantineheritage.com

Following the opening of the Bomonti beer factory, an eponymous beer garden was opened right next to the brewery. Customers of both sexes were allowed to bring food from outside and picnic on the vast greens or sit at the tables. Beer was served in a 5-liter cask with legs and specially designed glass steins. Bomonti Garden also hosted waltzes and concerts, and it resembled a carnival ground on the weekends in spring, with children playing all sorts of games as their parents enjoyed a cold beer or two under the warm Istanbul sun.

Although beerhouses enjoyed immense popularity in the late 19th century, their owners realized that by limiting their offerings to beer they were missing out on the opportunity to increase their revenues and profits. So, the likes of Şark Birahanesi (Orient Beerhouse) and Byzantium Beerhouse began offering French wine, vodka, whiskey, and rakı to their customers. These quasi-new establishments proved to be even more appealing to Istanbulites, and by the end of the first decade of the 20th century, Pera had already become home to a handful of chic bars.

The Occupation and Proliferation of Bars

Istanbul’s nights were not to be silenced.

The first significant increase in the number of bars in Istanbul occurred after the Russian Revolution, with White Russian emigres in Istanbul opening some of the most elegant establishments the city had seen so far, such as the Maxim Bar in Taksim. But it was with the occupation of Istanbul following the end of the First World War that the bars in Istanbul mushroomed tremendously.

Most bars were concentrated in Taksim and Şişli, but suburbs like Maltepe also welcomed these new establishments serving the British troops stationed in nearby camps. Some, such as the Britannia Bar were opened by demobilized British servicemen, and a few became successful franchises, like Christo’s Union Jack Bar, which had branches in Istanbul, Mudros, Imbros, and Salonica. Turkish entrepreneurs jumped on the bandwagon as well; as a few British journalists noticed, almost overnight, Pera was swarmed with bars named “English,” “Scottish,” “London,” or “Gibraltar.” Such was the magnitude of the bar craze that in 1921, Istanbul had 1413 licensed venues, of which 186 were bars – a per capita ratio close to that of London. Istanbul’s nights were not to be silenced.

Orient Bar, source: Pera Palas: Beyoğlu'nun Batılılaşma Hikayesi

Bomonti Steins, source: Osmanlı'dan Cumhuriyet'e Biraya Dair: Objeler, Belgeler, Fotoğraflar

Among these, the most majestic was the Orient Bar, situated in the Pera Palace Hotel, and its clientele showed. Offering the highest quality wines, beers, and whiskies, the bar attracted the likes of the Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Occupation Army, General Charles Harington who could be seen sipping away at a cold glass of Bomonti beer after spending the day playing cricket in Beykoz greens or swimming in Florya, on the northern shores of the Marmara Sea. And, perhaps even more importantly, Ernest Hemingway tried rakı for the first time in the Orient Bar in 1922 and is said to have been immensely impressed by the aftertaste it left in his mouth.

Park Hotel’s Bar was an informing meeting point for spies from all nations.

Studio Jean Weinberg, Park Hotel terrace, postcard, undated [c. 1931], source: archive.metromod.net

View of Park Hotel, Istanbul, date and photographer unknown, source: archive.metromod.net

Although the Orient Bar continued to appeal to many a celebrity, it was Park Hotel’s Bar, located near the German Embassy in Taksim, that drew an even more exciting crowd during the Second World War. In 1942, 17 different intelligence agencies converged on Istanbul and an intense but oddly intimate battle ensued between spies, who all knew their rivals’ identities by heart. And, Park Hotel’s Bar, where German Ambassador Franz von Papen used to enjoy the most expensive Cordon Rouge champagne while his British counterpart Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen preferred to sip his whiskey alone as he listened to the pianist playing his favorite Chopin sonatas, was their informal meeting point. So, when an intelligence officer from the Abwehr or MI6 entered the bar, the orchestra would start playing the most famous tune in Istanbul during the Second World War