From Wine to Rakı: An Introspective Journey by Istanbul’s Intelligentsia

From Raki Cask to Ahmet Rasim, source: Aydede

Although arak – a translucent and unsweetened Levantine spirit of the anise drinks family and hence, for many an aficionado, rakı’s primogenitor – had made its way to Constantinople by the middle of the 16th century, as poet Aşık Çelebi wrote in 1568: “The majority of those who frequent meyhanes in Galata and Tahtakale prefer wine to accompany the handful of delicious mezzes prepared on the premises by a master cook at one of the far corners of the tavern.”

Poet Baki, source: Wikipedia

Almost everything we know about the drinking culture in early modern Constantinople comes from Ottoman chroniclers, who, without exception, confirm wine’s status as the sovereign drink at the time. Take Baki, a poet from the early 16th century: “Although all food goes well with sherbet, kebab offers unsurpassable palatal delights when consumed alongside wine.” Or, an anonymous description of a late 16th-century meyhane named after its owner, Yani: “Most of its clientele were Divan poets like Ahi Çelebi, who would bring fresh mezzes he had bought in Balıkpazarı (fish market) and drink wine and sing with other poets for hours at end.”

Even as late as the beginning of the 19th century, wine continued to be the choice drink of the tavern clientele in Istanbul. Ayni Effendi of Antep, a poet and a meyhane habitué himself wrote: “The best meyhanes offer Erdek (Artàke) wine with duck kebab. You can often see a bunch of ulema sitting at a table adorned with ambrosial mezzes – caviar, pastrami, mussels, pickled fish, sardines, and cheese – drinking way more than they can handle and making a fool of themselves.”

Sir James Porter, source: Wikimedia

Selim II was rumored to have conquered Cyprus mainly because he had fallen into the grip of aromatic Cypriot wine.

Left: Selim II, source: Wikipedia, Right: Mahmud II, source: Wikipedia

It wasn’t only the tavern regulars who enjoyed the Bacchanalian elixir at every chance they got. As Sir James Porter, British Ambassador to Constantinople between 1747 and 1762, noted, countless prominent members of the Sublime Porte drank copious amounts of wine and chewed cinnamon sticks, celery ribs, or cloves to get rid of the alcohol breath. Likewise, many an Ottoman Sultan was known to savor wine such as Selim II (1566-1574), who was rumored to have conquered Cyprus mainly because he had fallen into the grip of aromatic Cypriot wine, or Mahmud II (1808-1839), who had Topkapı Palace’s cellars filled to the brim with casks of wine and who did not refrain from enjoying a glass or more in the presence of others.

From Arak to Düziko via Mastika

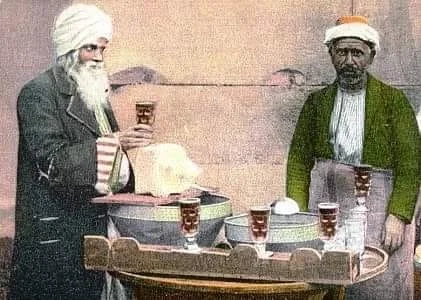

Arak seller, source: eksiseyler.com

Arak means “sweat drop” in Arabic, and the drink is thought to have been named so, as the drop of distilled alcohol at the cap of the alembic resembled a sweat drop. After arriving at the capital in the middle of the 16th century, arak was first sold in meyhanes and then, during the 17th century, also in specialized shops called arakçıyan. According to the famous Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi, among the most popular arak types in Constantinople were: aniseed, sweet, cinnamon, mustard, date, clove, linden, and Persian. Despite the existence of these specialized shops and the variety of flavors in which it was offered, arak never became as popular as wine – likely because wine arrived from nearby villages and islands and therefore cost much less than arak traveling from the Levant.

It was only at the beginning of the 19th century that the first popular kind of rakı emerged in the meyhanes of Istanbul: mastika. Seasoned with aniseed and mastic – a resin with a slightly cedar-like flavor gathered from the mastic tree native to the island of Chios, and hence called the “tears of Chios” – mastika’s popularity gradually increased throughout the first half of the 19th century even though it was never able to challenge wine’s dominance in the capital. Because it was distilled in Chios, it was still more expensive than wine and, according to Ahmed Rasim, the Istanbulite author and one of the leading rakı aficionados of all times, it had a heavy taste and smell, which did put some drinkers off. So, during most of the 19th century, mastika played second fiddle to wine, but in a way, while doing so, it paved the way for its sister, düziko to bring the eonic reign of wine to an end.

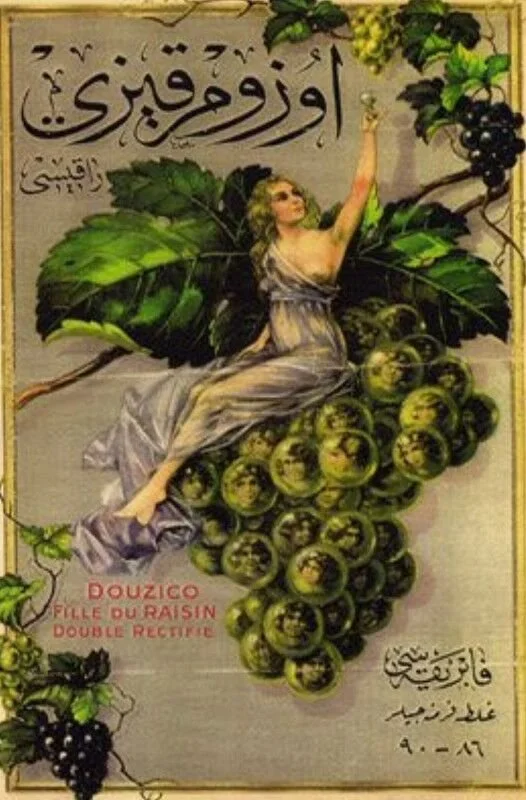

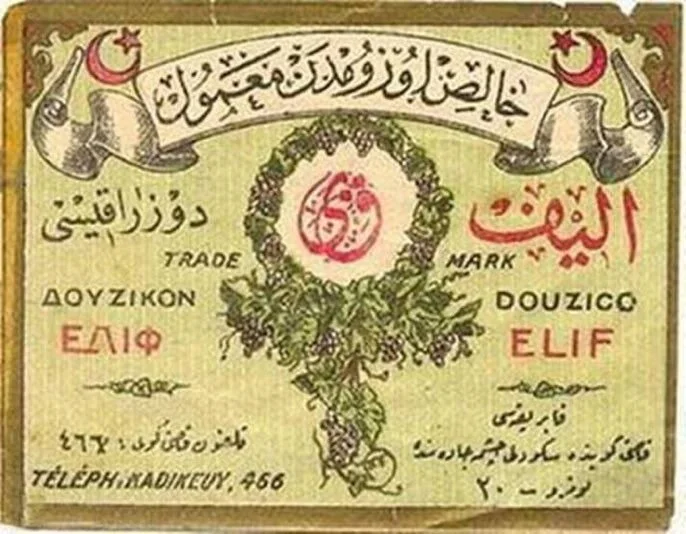

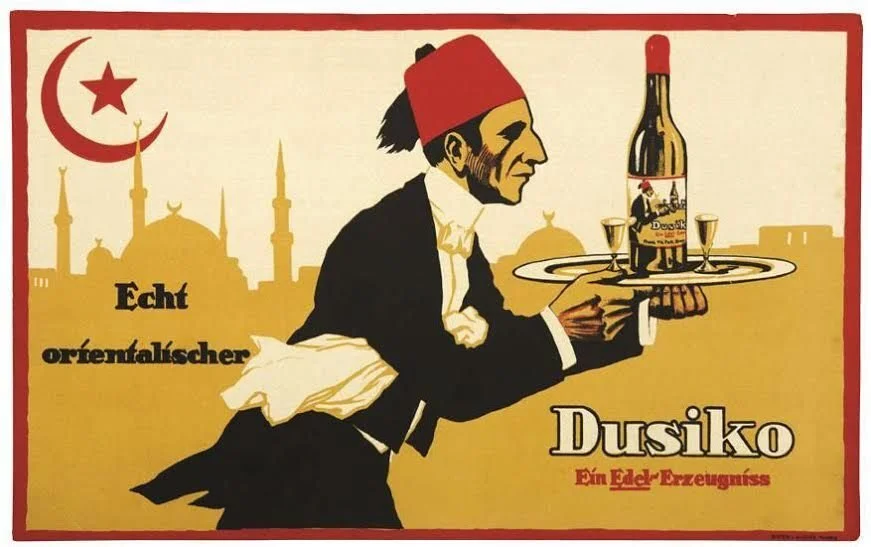

Douzico Raki ad, source: 100sene100nesne.com

The first düziko brand in the sense we understand the term today was Umurca. Established in the 1880s by Abdülhamid II’s chief chamberlain and ex-minister of trade, Ragıp Paşa, Umurca quickly became one of the most popular rakı brands in the capital. So much so that, at the turn of the century it came to rival the long-standing favorite of meyhane frequenters, Erdek rakı.

Düziko came from the word düz, meaning plain or straight; in the rakı lexicon, it described the kind of rakı that was flavored only with aniseed and which is the classical rakı sold in Turkey today. According to Rasim, during the early 1880s düziko replaced the traditional mastika with astonishing haste and ubiquity. As historian François Georgeon claimed, this was a pervasive shift – Istanbulites from all socio-economic strata, from the porters to artisans, from sailors to journalists, from the bottom of the ladder to the top, gave up the mastika in favor of the düziko. What was the reason behind this all-encompassing and dizzyingly rapid change?

The first explanation that pops into mind is economical - düziko was cheaper than not only wine but mastika as well. Following the Crimean War (1853-1856), the Sublime Porte had allowed distillation facilities to open and operate in Istanbul, which meant rakı could now be produced in the capital. And, as it was not flavored with a resin that could only be gathered from trees from the island of Chios, the cost of distilling düziko was substantially lower. Indeed, at the turn of the century, a glass of rakı cost only half as much as a glass of beer.

Ahmed Rasim explained his reasons for preferring düziko over other drinks in the following words: Beer is useless as all it does is fill you up. Wine is too light, and mastika too heavy. But, düziko? Düziko hits the spot. And, follow it up with a handful of roasted chickpeas, and gone is the alcohol breath!

However, explanations that over-rely on economic rationalities often miss the more nuanced aspects of the human psyche – as is the case here. After all, it wasn’t only the lower classes who eked out a living that cherished rakı but members of all classes, including the better-off bureaucrats and wealthy elites, who could easily afford mastika and wine. Something else was brewing in fin-de-siècle Istanbul that catalyzed this change – something that was reflected in but that cannot be reduced to the ascension of rakı to the throne.

Balıkpazarı 1890s, source: eskiistanbul.net

Balıkpazarı 1890s, source: eskiistanbul.net

As rakı declared its sovereignty, Istanbul’s meyhanes, once known by the wines they offered, came to be identified with the kinds of rakı they sold. Fertek Meyhanesi, a favorite locale in Balıkpazarı during the early years of the 20th century serves as a perfect example. According to Aşık Razi there were no tables on the premises as everyone drank at the counter and the owner didn’t serve any mezzes so customers brought their own. Despite these so-called inconveniences, the meyhane was frequented by the crème de la crème of Istanbul society. Why? Because it was the only establishment that served Miryofte rakı from Tekirdağ (in Thrace) and Fertek rakı from Niğde (in inner Anatolia).

An Existential Crisis

Raki ad from First World War, source: 100sene100nesne.com

Extensive Westernization reforms marked the second half of the 19th century. The empire was ailing, and nationalist movements undermined its claims to legitimacy. A sense of doom and gloom lingered in the air as very few imagined it possible to resuscitate the empire. If the empire was to come back from the dead, felt the intelligentsia, not only progress had to be achieved, but a sense of shared Ottomanness had to be inculcated in the diverse communities co-habiting the empire. So, on the one hand, the empire had to modernize-cum-westernize, and on the other, it had to preserve its identity, its Ottomanness – enter, rakı.

Drinking what came to be known as the “lion’s milk” came to signify civility while affirming Ottoman identity.

Different brands of raki from the turn of the centuryö source: eksiseyler.com

As François Georgeon aptly points out, it was no surprise that the change was spearheaded by Istanbulite bureaucrats, many of whom were also part of the city’s intelligentsia. Many had spent some time in one of the European capitals either as students or as parts of the Ottoman delegate. And it was these men burning with a desire to showcase their Europeanness alongside Ottomanness who were the first to not shy away from showing their faces at meyhanes; it was they who believed that public consumption of alcohol was a symbol of civilized behavior; and it was they, who thought of rakı as one of the integers that embodied the very essence of Ottomanness. And so, drinking what came to be known as the “lion’s milk” came to signify civility while affirming Ottoman identity.

Unfortunately, it was too little too late. Nationalism had amassed such strength in the 19th century that it was impossible for an identity like Ottomanness to stand on its path. So, despite all the aforementioned reforms, the Ottoman Empire continued to lose land to secessionist movements. And, so deepened the existential crisis Ottomans, but especially the thinkers and bureaucrats, found themselves in. Bekir Fahri wrote about the void they found themselves in because they did not know who they were and Yusuf Akçura bemoaned how “Serbs, Bulgarians, and Greeks – our subjects for five centuries – have beaten us because we cannot answer a simple question: ‘Who are we?’” Very soon, they came up with an answer to that question – they were and had always been Turks. And rakı was their national drink, as it always had been – unlike the mastika, one polemicist noted, which has such low levels of alcohol that only henpecked husbands would drink it.

Further Readings

Ahmet Rasim. İstanbul’da Eğlence Hayatı. İstanbul: Maviçatı. 2017.

Daniel Goffman. The Ottoman Empire and Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2002.

François Georgeon. Rakının Ülkesinde: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’ndan Erdoğan Türkiye’sine Şarap ve Alkol (14. - 21. Yüzyıllar). İstanbul: İletişim. 2021.

Meyhane İhtisas Kitabı. A’dan Z’ye Meyhane: Nedir, Nasıl Çalışır? İstanbul: Anason İşleri. 2022.