The Coffeehouse – An Iconic Urban Fixture

Coffee made its way to Constantinople from Yemen via Jeddah and Cairo in the mid-16th century. Shortly after the arrival of the beans that instantly became an obsession with Istanbulites, the first coffeehouse in the imperial capital was opened.

Mocha, in Arabien. (View of Mocha, Yemen.) by by Gaspar Bouttats (1640-1695), source: Paulus Swaen Inc

According to the Chronicles of Peçevi, two entrepreneurial Syrians called Hakm and Shams opened the first kahvehane in Tahtakale in 1554. Thanks to its cosmopolitan complexion (majority of its residents were Persian, Indian, North African, and Spanish Jew), links to trade ports in the Golden Horn, and magnetism for sailors passing through the city, Tahtakale proved to be an ideal breeding ground for the coffeehouse. Within the year, more than a handful of coffeehouses had cropped up in the neighborhood, and shortly thereafter, other boroughs followed suit, bringing the number of similar establishments in the city to 50 by 1560 and 600 by the end of the century, according to Swedish Ambassador Ignatius D’Ohsson.

Tahtakale engraving, source: Kurukahveci Mehmet Efendi Website

Hungering for Socialization

The coffeehouse was a catalyst for the extrovertization of life in Constantinople.

Spaces where urbanites could socialize in 16th-century Constantinople were found wanting. Mosques were not for entertainment, Muslims were (at least officially) prohibited from enjoying meyhanes (taverns), and there were no restaurants in the modern sense of the word, meaning the overwhelming majority of the population led introverted lives. The immense and immediate popularity enjoyed by the coffeehouse was a testament to the Istanbulites’ desire to change that. So, the coffeehouse provided the urbanite with an excuse to do something he obviously already had the urge to do: to live outside, to spend time in the company of his fellows, to be entertained, to see and be seen – in short, to socialize.

The coffeehouse was not a locale to merely consume coffee but a space of entertainment, camaraderie, conversation, and even learning. It was, in a sense, a catalyst for the extrovertization of life in Constantinople.

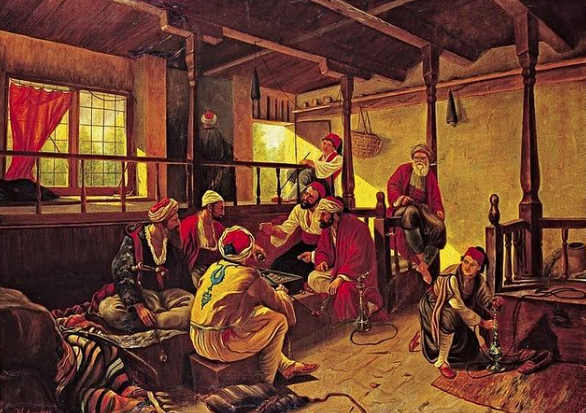

Ottoman Coffee House 1862 by Preziosi, source: wikicommons

According to Ottoman polymath and encyclopaedist Katip Çelebi, a.k.a. Hajji Khalifa, there was at least one coffeehouse on every street in 17th- century Istanbul. By the 19th century, there were approximately 2,500 coffeehouses in Istanbul, which led traveler Edmondo de Amicis to conclude: “Wherever you are in Constantinople, there is a coffeehouse at most three minutes away from you.” How did the coffeehouse not only maintain but increase its popularity over the centuries? Simple: by catering to varying needs and demands of Istanbulites from different walks of life.

Ottoman period coffee pot with foldable handle, source: Bayrak Auction

A well-made cup of Turkish coffee is indeed the most delectable beverage that can be imagined.

For centuries, there have been no changes in the way Turkish coffee is prepared. The copper kettle, called cezve, is shaped like an ewer and is tinned inside and out. The very finely ground coffee is brewed by boiling in the cezve, whose broad base receives more of the flame, allowing the water to come to a boil quickly. The narrow opening retains the volatile essence of the brew, which is what truly sets Turkish coffee apart. As the Londoner Charles White who lived in Constantinople for three years during the first half of the 19th century noted: “Those who overcome the first introduction prefer it to that made after the French fashion, whereby the aroma is lost or deteriorated. A well-made cup of Turkish coffee is indeed the most delectable beverage that can be imagined; being grateful to the senses and refreshingly stimulant to the nerves.”

A Multifunctional Space

A cafe in Istanbul between 1850 and 1882 by Amadeo Preziosi, source: wikicommons

At all hours of the day, picturesque crowds of loungers may be seen enjoying meditation or conversation in coffeehouses spread all over the city.

Coffeehouses in Istanbul were often large buildings made of stone. Most of them had the wall facing the street down to place stools or even benches on the street when weather permitted. Especially in the summer months, so tightly packed were the city’s streets with customers sipping away at their coffee while enjoying their chibouk that it was virtually impossible to walk through them. Utilizing the streets (and other public spaces) in this manner created an organic unity between the city and the coffeehouse, whereby the borders between the two, inside and outside vanished.

Illustration from Constantinople and the Scenery of the Seven Churches of Asia Minor illustrated…, With an historical Account of Constantinople, and Descriptions of the Plates…, London/Paris, Fisher, Son & Co. (1836-38), by Robert Walsh and Thomas Allom, source: wikicommons

A Coffee House in Tophane, source: wikicommons

The locus of interior design and furnishings was the habitués’ comfort and not functionality. The upholstered divans surrounding the room were overlaid with colorful cushions and pillows. The fountain in the middle of the room provided a soothing trickle – not dissimilar to Hypnos’s magical wings – that led the loungers into the sweetest slumber. Chibouks made from cherry trees lined up the walls, and the patron, known as the kahvedji, was often found at one corner working with bellows, ensuring that the kindling was continually aflame.

It is a historic image. From probably 16th century Ottoman Miniature, source: wikipedia

This 16th-century Ottoman miniature shows all the typical activities that took place in an Istanbul coffeehouse. On the top are men drinking freshly brewed coffee (by the patron on the top right) from tiny porcelain cups. Right beneath them are men of letters, some engaged in reading and some in literary discussions. To their left is another group of men occupied with less high-minded conversations, as the lack of books indicates. Beneath them are a couple of musicians – one playing a tambourine and the other a kamancheh. To their right are men playing backgammon and mangala (a traditional Turkish mancala game). And last but certainly not least, the meddah (storyteller) stands in the middle, narrating a story to an audience (on his right) attentively listening to his every word.

Alois Schönn - The Game of Backgammon 1870, source: MutualArt

“At all hours of the day, picturesque crowds of loungers may be seen enjoying meditation or conversation”

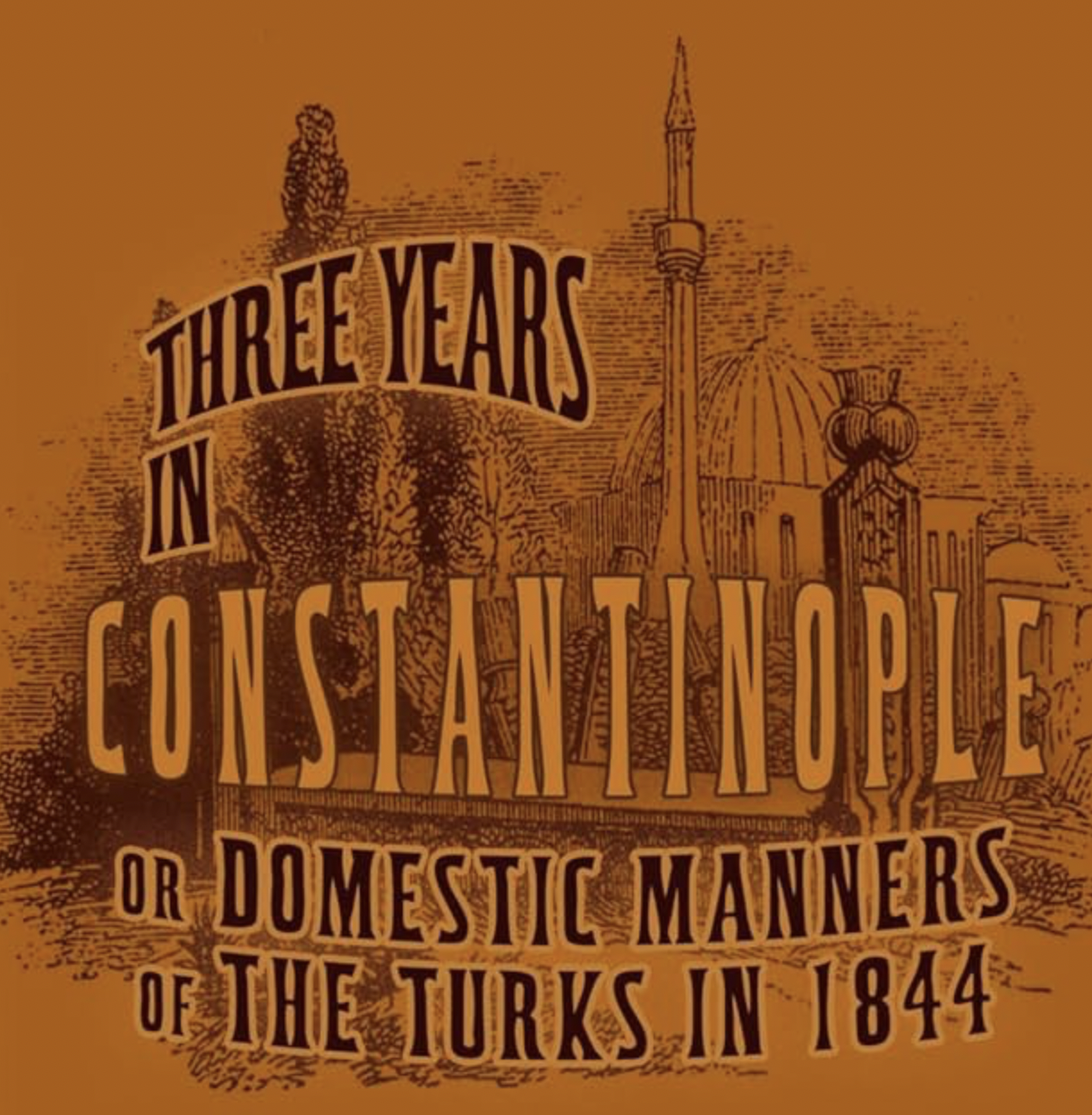

White's book cover

19th-century travelers' accounts also attest to this multifunctional character of Constantinople’s coffeehouses. Charles White notices that “At all hours of the day, picturesque crowds of loungers may be seen enjoying meditation or conversation” in coffeehouses spread all over the city. The more time he spends in these establishments, the more he likens them to middle-class clubs in Western Europe: “They all have regulars, who discuss private and public affairs, or divert themselves with stories of a meddah or shrill songs of gypsy musicians.”

John Hobhouse. source: Royalsociety.org

Almost every single traveler who visited Istanbul singles out “taking keyif” as the defining characteristic of the coffeehouse. Keyif can best be described as a relaxed, unrushed, or even prolonged enjoyment, and Istanbulites’ patient pursuit of it never ceases to amaze the flaneurs. Take John Hobhouse, who visited Constantinople at the beginning of the 19th century. His companion took him to “one of the better” establishments in Yenikapı, on the southern shore of the historical peninsula: “Several well-dressed Turks with pipes were listening to the pretty airs of a guitar and violin while the recesses were with others asleep…Indeed, none of the guests seemed entirely awake, but inhaling the odors of their perfumed herbs, silent, sedate, and lost in the delicious bliss of inactivity, were lulled into the soft approaches of repose by the tinkling music, the unceasing fall of the fountain and the regular rippling of the water on the sea shore.”

During his travels to Constantinople in 1899, Norwegian author Knut Hamsun visited one of the coffeehouses he had heard so much about. Although he was accompanied by a woman, no one inside seemed to take notice of their presence. Men, in fez and reclining on the red cushions scattered all over the divans, and with their feet tucked under, drank their coffee and smoked. Hamsun and his friend decided that aping the locals was the best course of action so, they took a sip, gave the tiny cup a shake, drank the dregs, leaned back, and gazed at the ceiling. “Europe has forgotten how to enjoy life,” mused Hamsun: “The Turk, on the other hand, despite being so close to Europe, insists on continuing to take keyif.”

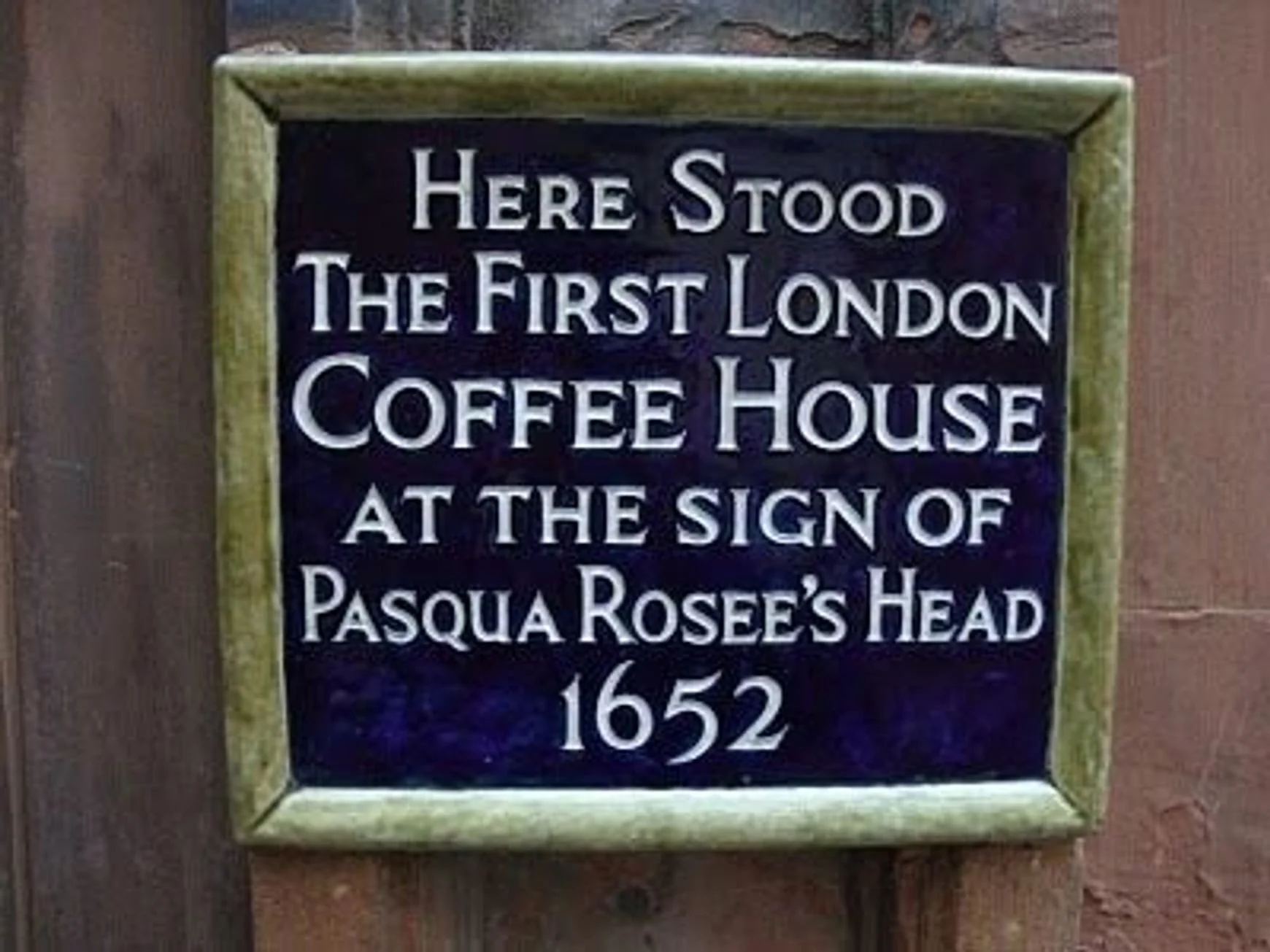

The Turk’s Head

Upon returning from their journeys to Constantinople, British travelers of the late 16th and early 17th century described how “the Turk, forbidden by Mohammed to touch intoxicating liquor, was accustomed to drink an aromatic concoction, black in color, made by infusing the powdered berry of a plant that flourished in Arabia.” Everyone in Istanbul, “irrespective of age or rank,” drank it, they were bemused. So, by the time an Ottoman Jew originally from Smyrna opened England’s first coffeehouse in 1650, at the Angel in the parish of St. Peter, Oxford, the British public was already hyped about this Oriental drink.

Blue Plaque, source: Layersoflondon

Dallam boarded the 300-tonne Hector in Grave’s End, Plymouth on February 9th. The organ’s disassembled parts were placed in crates and kept in the hold. The journey to Constantinople took a little more than six months, and Hector anchored in the Golden Horn on August 15th. The crates were moved to the Ambassador’s house in Galata – “among the beautiful vineyards of Pera,” wrote Dallam in his journal – on the 17th. When the embassy staff opened the crates, to his dismay, Dallam noticed that “the glowing work had all decayed because it had lied in the humid hold of the ship for more than six months” and even more worryingly, quite a few of the metal pipes were either bruised or broken. The Ambassador, convinced that the organ could not be restored to its glory, was inconsolable. But, Allam, known for his industriousness and masterful handwork, finished repairs by the 30th – “It looks as good as new,” he rightfully gloated in his journal.

1820s - Jacob's CH location in Oxford, , source; British Museum

Quite a few of London’s coffeehouses sold beverages other than coffee. According to John Tatham’s anti-coffeehouse play titled Knavery in All Trades; or, The Coffeehouse, a Comedy, Londoners particularly fancied the chocolate: a steaming mixture of chocolate grounds, eggs, sugar, and milk served alongside a thin slice of bread. Other offered alcoholic beverages such as mead (made by fermenting honey mixed with water), cider, perry (fermented pears), usquebaugh, aqua vitae (a fashionable, odorless, colorless alcoholic drink), beers, and ales.

London coffeehouses rose to prominence because they were accessible to Londoners from all classes and strata.

The inside of a typical London coffeehouse also resembled a tavern. The interior was decorated almost entirely in wood, and most proprietors lived on the premises. And, although some affluent ones offered accommodation, most of the coffeehouses comprised a large room with multiple tables. Several servants, often younger boys, served freshly brewed coffee made with water from the Thames, while others, such as shoe shiners, also plied their trade on the premises.

War of the Sexes

London coffeehouses rose to prominence because they were accessible to Londoners from all classes and strata. As one anonymous pamphlet from the 1700s noted: “One penny was all that was needed by any man, rich or poor, to gain entry. People who had scarcely two pence to buy bread spent a penny each evening in coffeehouses.” Puritan owners drew attention to the same fact in the rules they hung up at the entrance to their establishments: “Preeminence has no place here, so you can sit anywhere you want, and you do not have to rise for anyone.” However, the most ferocious remonstrations did not come from proponents of traditional social boundaries but from women who, during the second half of the 17th century, waged a war of words against their husbands.

Women's Petition Against Coffee, an anonymous pamphlet published in London in 1674, source: wikipedia

In 1674, an anonymous pamphlet demurely titled “Women’s Petition Against Coffee” was published in London. The message was anything but: “Due to coffee, the sensible English vigor is in jeopardy…English men have become mere cock-sparrow, fluttering things…not capable of performing their devoirs which their duty and our expectations exact…Our husbands are bandied to and fro all day between the coffeehouse and the tavern, whilst we poor souls sit moping all alone ‘till 12 at night…which forces us to take up this lamentation and sing:

Tom Farthing, Tom Farthing

Where hast thou been Tom Farthing?

Twelve o’clock you come in

Two o’clock you begin

And then at last can do nothing!”

Seeing that their newly adopted lifestyle was under threat, men responded with their own anonymous pamphlet conveying a more concise message: “Coffee is the general drink in Turkey and men of those regions are very active and eager performers in the sports of Venus!”

Resim Altı Yazısı: Original Caption: “I had the honor of bringing Mr. Pope up to London, from our retreat in the forest of Windsor, to dress à la mode, and introduce at Will’s Coffee Room.”, source: Art Renewal Web Site

Coffeehouses in London were also known as Penny Universities, because they functioned as informal education centers for young poets, musicians, and other men of science and letters, and coffee only cost a penny. One of the most famous of these was owned by William Urwin and known simply as Will’s. Located on Russell Street and centering on the figure of John Dryden, Will’s was the place to be in the late 1600s for anyone who aspired to become a poet or playwright. Similar establishments existed in Ottoman Istanbul. Known as kıraathanes (literally, reading house), these 19th-century coffeehouses offered their clients dailies and periodicals, and most of them had libraries full of books that reflected their regulars’ interests. Sarafim, located in the old quarter and frequented by literary giants such as Namık Kemal and Ahmet Rasim, was the most revered kıraathane of its time.

Enter Meddah, the Indubitable Star of the Coffeehouse

Although coffeehouses had become a staple of London’s social life in the 18th century, British travelers continued to be amazed by Istanbul’s kahvehanes well into the 20th century. The reason for this was the presence of a figure that according to Walter Benjamin – one of the most original thinkers of the 20th century – had long become something remote, distant, or even alien to European culture: the storyteller.

Meddah storyteller, souce: wikipedia

The meddah was capable of enacting several characters from all walks of life with mesmerizing fidelity.

Thomas Allom, source: wikicommons

Meddah, however, was no ordinary storyteller. Unlike troubadours, who often recited epic war stories, and moralists, who narrated Islamic tales, the meddah had an astonishing repertoire. According to Thomas Allom, who visited Constantinople in 1834, the meddah was capable of enacting several characters from all walks of life with mesmerizing fidelity, adopting different countenances, attitudes, and phraseology for every one of them.

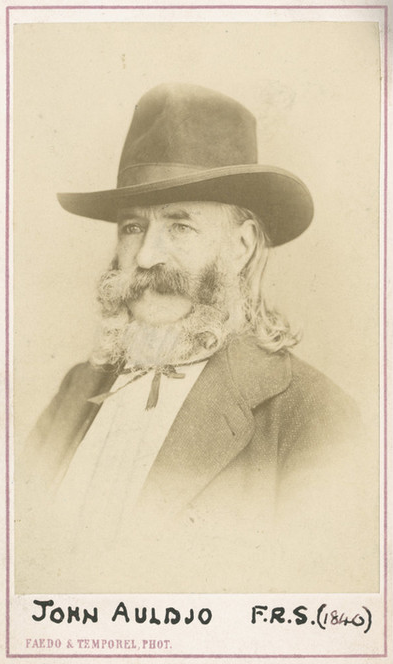

John Auldjo, source: Royalsociety.org

John Auldjo, who was in Istanbul in 1833, gave one of the most comprehensive accounts of a meddah performance in English. The coffeehouse where the storyteller would take the stage was located on the shores of Samatya. After arriving at the kahvehane, they sat “in the open air, one a long pier of wood built into the sea, where there were hundreds perched upon low stools, smoking or eating delicious custard, and laughing and talking with more vivacity than” he could have expected in “beings generally so taciturn.” After a short while, a man approached the crowd and clapped his hands, signaling that the performance was about to start. Inside, the seats were arranged in a semicircular form as in a theater, and noticing that Auldjo and his companions were in European costumes, the locals “very politely” offered them seats in front. In a few minutes, a man carrying a stick as his only prop and wearing a magnificent ring purportedly gifted by the Sultan was helped to the top of a platform amidst universal, deafening applause. Once atop the platform, a profound silence greeted him; everyone was anxiously waiting to be entertained. He then told his story – apparently titled “At Home” – mimicking several characters and contorting his body in ways Auldjo thought unimaginable. The audience, more than pleased with what they saw, showered the meddah with exclamations of delight and generous tips. So captivating had the performance been that many among the listeners had committed the cardinal sin of not drinking their coffee when steaming hot, Auldjo noticed on his way out.

Further Readings

Ahmet Yaşar (ed.) Osmanlı Kahvehaneleri: Mekan, Sosyalleşme, İktidar. Istanbul: Kitap Yayınevi. 2009.

Aytoun Ellis. The Penny Universities: A History of Coffee-Houses. London: Secker & Warburg. 1956.

Brian Cowan. The Social Life of Coffee: The Emergence of the British Coffee House. New Haven: Yale University Press. 2005.

Charles White. Three Years in Constantinople; or, Domestic Manners of the Turks in 1844. London: Henry Colburn. 1846.

John Auldjo. Journal of a Visit to Constantinople and Some of the Greek Islands in the Spring and Summer of 1833. London. 1835.

John Hobhouse. A Journey through Albania and Other Provinces of Turkey in Europe and Asia to Constantinople during the years 1809 and 1810. London: James Cawthorn. 1813.

John Tatham. Knavery in all Trades; or, The Coffeehouse, a Comedy. 1664.

Lady Emelia Hornby. Constantinople during the Crimean War. London: Richard Bentley. 1863.

Nabil Matar. Islam in Britain, 1558-1685. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1998.

Ralph Hattox. Coffee and Coffeehouses: The Origins of a Social Beverage in the Medieval Near East. Seattle: University of Washington Press. 1988.

Robert Walsh. A Residence at Constantinople, during a Period Including the Commencement, Progress, and Termination of the Greek and Turkish Revolutions. London: Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. 1836.

Thomas Allom. Constantinople. London: Fisher Son & Co. 1859.