Littérateur - Learned Istanbulites as Regulars

Cumhuriyet Meyhanesi in 1941, source: 100tarihilokanta.com

Many of Istanbul’s littérateurs had not one but a few (sometimes even a handful) of favorite meyhanes. Perhaps because they spent quite some time in meyhanes and liked an occasional change of scenery. Maybe every meyhane answered another aspect of their desire to have a home away from home. Or, they loved the barbas and other regulars of each in their own way and wanted to spend as much time together as possible. Whatever the reason, the meyhanes they frequented had an indisputable impact on their work.

Sait Faik Abasıyanık

Sait Faik Abasıyanık in a garden meyhane, source: NTV.com

Regarded one of the giants of Turkish literature Sait Faik Abasıyanık’s (1906-1954) stories focused on life in the city and especially Istanbul’s denizens and the torments they experienced. He was the flaneur par excellence, who spent almost all his time outside meyhanes and coffeehouses promenading in Beyoğlu and at movie theaters, observing his fellow Istanbulites.

Eski Dostlar, source: kitantik.com

During the early 1940s, Istanbul provided refuge to countless Europeans who fled the war, and according to Abasıyanık’s friend journalist Sadun Tanju, the writer relished the time he spent in Beyoğlu whose streets would be buzzing once the sun set down. Meyhanes (like movie theaters) provided further sanctuary to people who, despite Turkey’s neutrality, still suffered the pain of the war right through their bones, providing them a space where the harsh realities of daily life could not seep through.

Salah Birsel, source: selyayincilik.com

Although Sait Faik left a trace, a mark in almost every meyhane in Beyoğlu, two of those occupied a special place in his heart: Nektar and Lambo. Nektar was a three-story meyhane, with high, standing tables at the entrance floor, regular seating arrangements in the middle, and a dancing floor at the top. According to his friend Salah Birsel, Sait Faik fell in love with a 19-year-old Rum woman called Alexandria in Nektar. The two did not meet by happenstance though – Rum waiter Yani, responsible for the second floor and a true meyhane great who knew all the regulars inside out, arranged their meeting. Abasıyanık makes latent references to Alexandria in his stories, but only under the names of Yorgiya and Eleni. The only place he refers to Alexandria by her real name is his poem addressed to Yani, A Table.

Set us a table, Yanakimu.

For me and my Alexandria

A table

With no flowers

Covered by old newspapers

Let our love and dreams

Flow free like wine

Let Alexandria play harmonica

With her dark fingers

Songs with simple melodies

And simple tunes

Let our meyhane smell of bitter olive oil

And you, Yanakimu; you, enjoy yourself.

Sait Faik with Arif Yesari at Cumhuriyet Meyhanesi, source: Facebook

Cumhuriyet, located in Beyoğlu’s fish market, was another meyhane Sait Faik frequented. Rumored to be christened by the founder of the republic Mustafa Kemal, who had a regular table there, Cumhuriyet attracted leading artists such as Cahide Sonku, Melih Cevdet Anday (who had enjoyed noon rakı with his friends every Wednesday), Ece Ayhan, Sevim Burak, and Oktay Akbal (who always picked the same three mezes: feta cheese, aubergine salad, and Russian salad). Cumhuriyet’s three headwaiters – cousins all named Ali – were the stars of the show in the meyhane during the post-Second World War era – so much so that poet Ece Ayhan called his favorite place “The Meyhane of Three Alis.”

Lambo – a bohemian lab

Lambo by Furkan Nuka Birgün, source: meyhanedeyiz.biz

According to one of his closest friends and one of Turkey’s greatest-ever artists, Abidin Dino, Lambo was one of the precious few places Sait Faik did not doubt his own being and felt free to become himself. It was as if he had his first happy day on this earth in Lambo, and only in Lambo was he able to enjoy his own being. Although there is no explicit reference to Lambo in his work (perhaps because it played such a key role in defining who he was that Abasıyanık found it too overwhelming to reflect on in his stories), this meyhane that actor/regular Mücap Ofluluğu called “a bohemian lab” remained e mecca for him and other littérateurs for years.

Throughout the 1940s and 50s, Istanbul was being rebuilt, redefined, and reappropriated in every sense. Immigration from Anatolia, the policies of the socially conservative and economically liberal Democratic Party, the unstoppable rise of nationalism, and resulting xenophobic acts of violence against the minorities in the city meant Istanbul had become an unrecognizable, alien, and even threatening place for many of its inhabitants. Lambo – “a gift to Turkish littérateurs” in author Rıfat Ilgaz’s words – appeared as a sanctum for poets, writers, artists, stage actors, art students, and many others who found themselves lost amidst this barrage of change.

Monsieur Lambo, source: Twitter

Interestingly, this haven was only as big as a tram and could accommodate no more than 20 regulars at a time. Its barba, Monsieur Lambo was such a distinctive character that littérateurs of the era found his appeal irresistible. Believed to be either a White Russian or a Rum who migrated to Istanbul following the Bolshevik Revolution, Monsieur Lamba always wore a tie, a vest, and oversleeves, and carried a pen behind his ear to keep tabs up to date. According to Ömer Uluç, who once said he met all his good friends at Lambo, he was a typical Byzantine with a long face and a pointy nose underlined by a meticulously trimmed pencil mustache. Apparently, he had suspicious, beady eyes, which led some to speculate that he was a Soviet spy stationed in Istanbul. Monsieur Lambo was, by all accounts, also a very cultured and elegant man who read Gogol, Dostoevsky, and Pushkin in Russian behind the counter when the meyhane wasn’t busy. Unfortunately, this “man of few words but many talents” took his own life after the shoe business that he opened following the closure of Lambo went bankrupt.

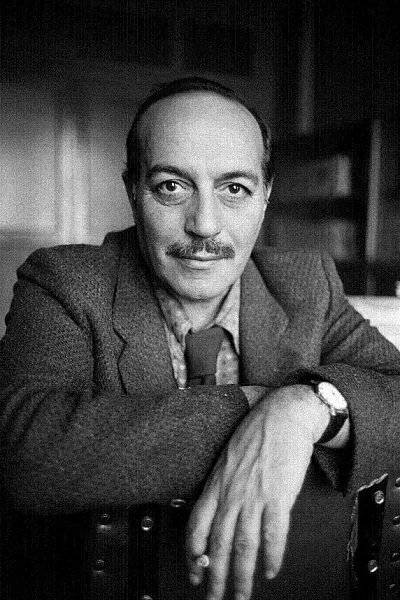

Özdemir Asaf, source: karar.com

Ernest Hemingway, Cuba 1946, source: wikimedia commons

Poet Özdemir Asaf loved rakı so passionately that he opened a meyhane in Bebek. Teeming with literary figures at all hours of the day, the meyhane also functioned as a writing studio for Asaf, who, like another regular from another world, Ernest Hemingway, “wrote while drunk and edited when sober.” Eşref Şefik was another man of letters who ran a meyhane. Durbaş and his friends would take their seats at the meyhane near the Golden Horn before the evening descended and would enjoy a bottle or two of mastic rakı alongside pilaki, fava, radishes, and feta cheese served in tea saucers.

Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı

Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı (1910-1956) was a poet, author, and translator of immense talent and an ardent supporter of the “art for art’s sake” movement. His poems focused on motifs such as death, lost love, loneliness, existential torments, and a longing for his childhood. One of his favorite meyhanes, for about two years during the early 1940s, was in Afrika Han on İstiklal Street near Grande Rue de Péra. Although we do not know the name of the meyhane, thanks to poet Baki Süha Ediboğlu’s recollection of the time he met Tarancı, we know Cahit Sıtkı was not only a regular but also brought the meyhane to life in one of his stories.

Cahit Sıtkı Tarancı, source: Wikipedia

The meyhane, located at the lower level of the Han, was small, cheap, and cozy. In three short minutes, their marble-top round table was teeming with mezes in tiny plates, and presently, a small bottle of Bahçe brand of rakı also found its way there. The headwaiter, a stocky figure in his late 40s, was busy as a bee, carrying three plates in each of his tiny hands and garnishing tables in the blink of an eye. Not even for a second did this Russian drop his smile, and although he attended to every customer with great care, it was evident that his reverence for Tarancı was on another level.

The headwaiter was none other than Mavromatis Efendi, the main character in Tarancı’s eponymous story. In it, Tarancı resembled the meyhane to a ship and the regulars to its passengers. “With a posture reminding you not of a creditor ready to strangle you but an aide-de-camp waiting for the pleasure to serve, and his ever-present smile,” Mavromatis could fill a marble table with all your favorite mezzes and rakı in a few minutes before you could even utter a few words. Mavromatis was the captain, Tarancı says, and he took the poet and his fellow frequenters on amazing journeys. And as regulars, they trusted Mavromatis as a passenger would trust her captain – knowing without a doubt that they would always be safe in their home away from home.

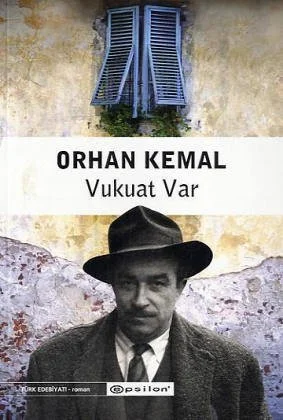

Orhan Kemal, Vukuat Var, source: Epsilon

Orhan Kemal was a regular of the Adana Kebabevi in Sirkeci. He believed one had to work hard over the years to enjoy rakı to its full extent. When he had the financial means, he’d visit his favorite meyhane and have turbot (which was rather expensive), shepherd’s salad, and cacık alongside his rakı. No wonder many of his stories (such as Vukuat Var) involve characters who, the instant they get hold of some money, make their way to a meyhane and enjoy the tastiest mezes and rakı, only to return to their impoverished lives the next day.

Orhan Veli Kanık

The sheer genius behind the line, “I wish I were a fish in a rakı bottle,” Orhan Veli Kanık (1914-1950) was one of the founders of the Garip Movement with Cumhuriyet regulars Oktay Rıfat and Melih Cevdet Anday. Orhan Veli resembled a Nietzschean tragic hero, an equally destructive and constructive force setting out to do away with all tradition while concurrently bringing about a new poetic aesthetic.

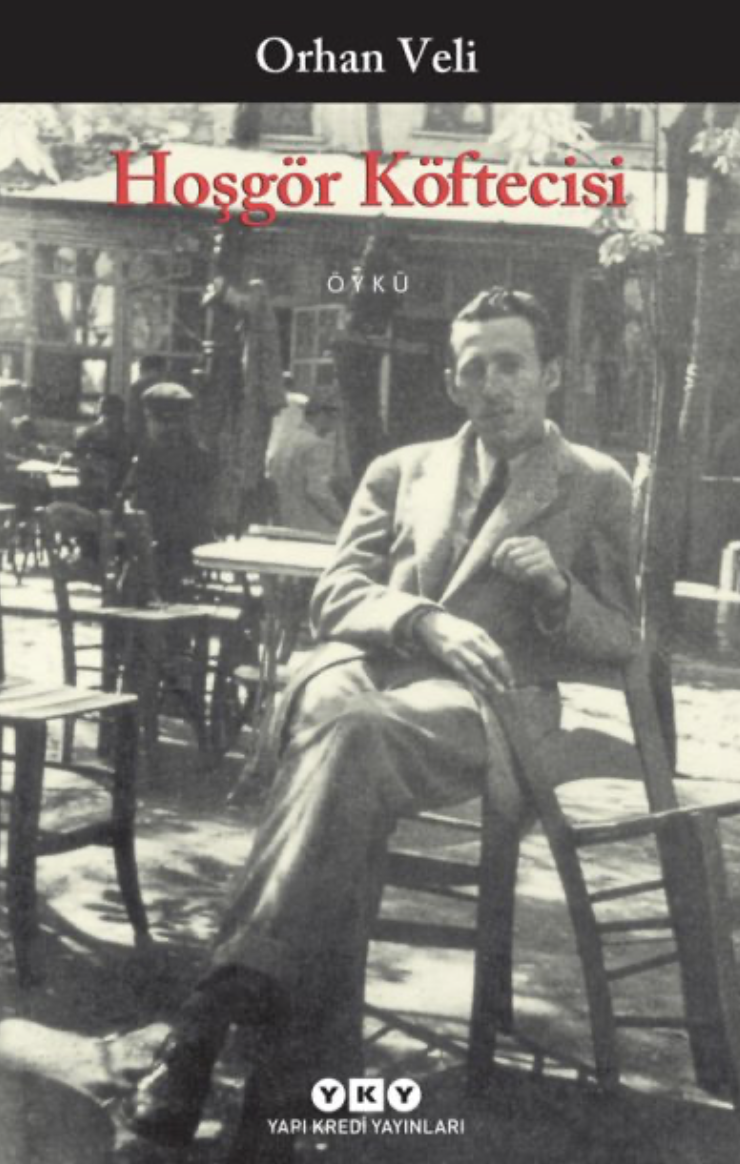

Orhan Veli, source: AA

Kanık’s favorite meyhane in Istanbul was called Hoşgör, although everyone referred to it by the name the poet deemed fit: Çat Çat. (Çat, when used in the idiom çat kapı gitmek, implies visiting a place without pre-planning, out of the blue, whenever one wants – which, of course, is the very nature of the relationship between a regular and her meyhane.) Kanık was such a regular that the likes of Sabahattin Ali (one of the two Turkish novelists – with Ahmet Hamdi Tanpınar – whose works were published by Penguin Classics) and Bedri Rahmi Eyüboğlu (Turkish painter and poet) would drop in Çat Çat at all hours of the day, knowing that they were more likely to find Kanık in the meyhane than in his house. Hoşgör had such an important place in Orhan Veli’s life that the poet made it the subject of one of his short stories published posthumously.

HOŞGÖR KÖFTECİSİ, Orhan Veli, source, YKY

In the eponymous story, Hoşgör is a fishermen’s meyhane with three wooden tables. Our protagonist discovers it in the unlikeliest of locations and, taking a leap of faith, decides to enter. At first, the constant screaming of the kitchen mistress Mualla bewilders him, but soon he gets so used to it that when she keeps quiet for 10 or 15 minutes he feels awkward, incomplete even. As he drinks his wine, he realizes he loves everything about Hoşgör and revisits the meyhane “time and again to become a part of this world.” He sings alongside Mualla, chats with the barba, and befriends “even the wooden tables, the narrow divan that stretches along the wall, and the rickety stools.” He learns what troubles the fishermen and the boat owners and listens to the stories of other regulars. And just like the protagonist in Tarancı’s story, every time he enters the meyhane, he feels like he is embarking on an incredible, marvelous journey all over the world – a world that mesmerizes him with its beauty. The moral of the story? “If you long to live in a wonderful world, find yourself a wonderful meyhane.”

Cemal Süreya

Cemal Süreya, source: Wikipedia

Cemal Süreya (1931-1990) was a notable member of the Second New Generation of Turkish poetry – an abstract, postmodern movement whose members included Edip Cansever, İlhan Berk, Ece Ayhan, and Ülkü Tamer. Süreya was the only member of the movement residing in Kadıköy and his favorite meyhane was called Hatay.

In the aftermath of the 1980 coup d’état, the military junta took draconian measures to suppress left-leaning, progressive thinkers, artists, and littérateurs. In this stifling atmosphere, when they needed to be with their comrades more than ever, many of these figures had to withdraw into their shells. In those years, Hatay emerged as one of those rare, precious spaces that allowed them to drink in solidarity, continue their camaraderie, and dream of a better future together.

Hatay Meyhanesi source: Gazete Kadıköy

Author Behzat Ay discovered Hatay and invited Süreya to join him one day, unaware that this invitation would change the destiny of the meyhane forever. As Süreya became an irredeemable regular, Hatay was transformed into a mecca for authors, poets, painters, singers, actors, and thinkers. Süreya convinced the owner of the meyhane to place a notebook for his guests on the premises. This notebook narrates the story of not just Hatay, but also the last two decades of Turkish poetry, painting, and intellectual life.

In the diary he started keeping five years before his death, Süreya, who was a solitary man of habits, explained what Hatay meant for him and others: “Hatay was a drinking house whose walls were adorned with magazine pages, authors’ scribbles, and artists’ photographs. It was the only meyhane with a notebook. Drawings, poetry, and memories graced the pages of that notebook. It was also a coffeehouse where I wrote many a piece. My letters would even arrive there. During the last five years, I’ve been at Hatay every Friday, sometimes twice or thrice a week. Hatay is a meyhane with its distinct rituals, a meyhane where an ex-minister shares a table with a university student.”

And London…

Istanbul was (and is) not the only city with its littérateur regulars. London is also swarmed with pubs frequented by literary figures, who could not resist spending hours at an end in their home away from home.

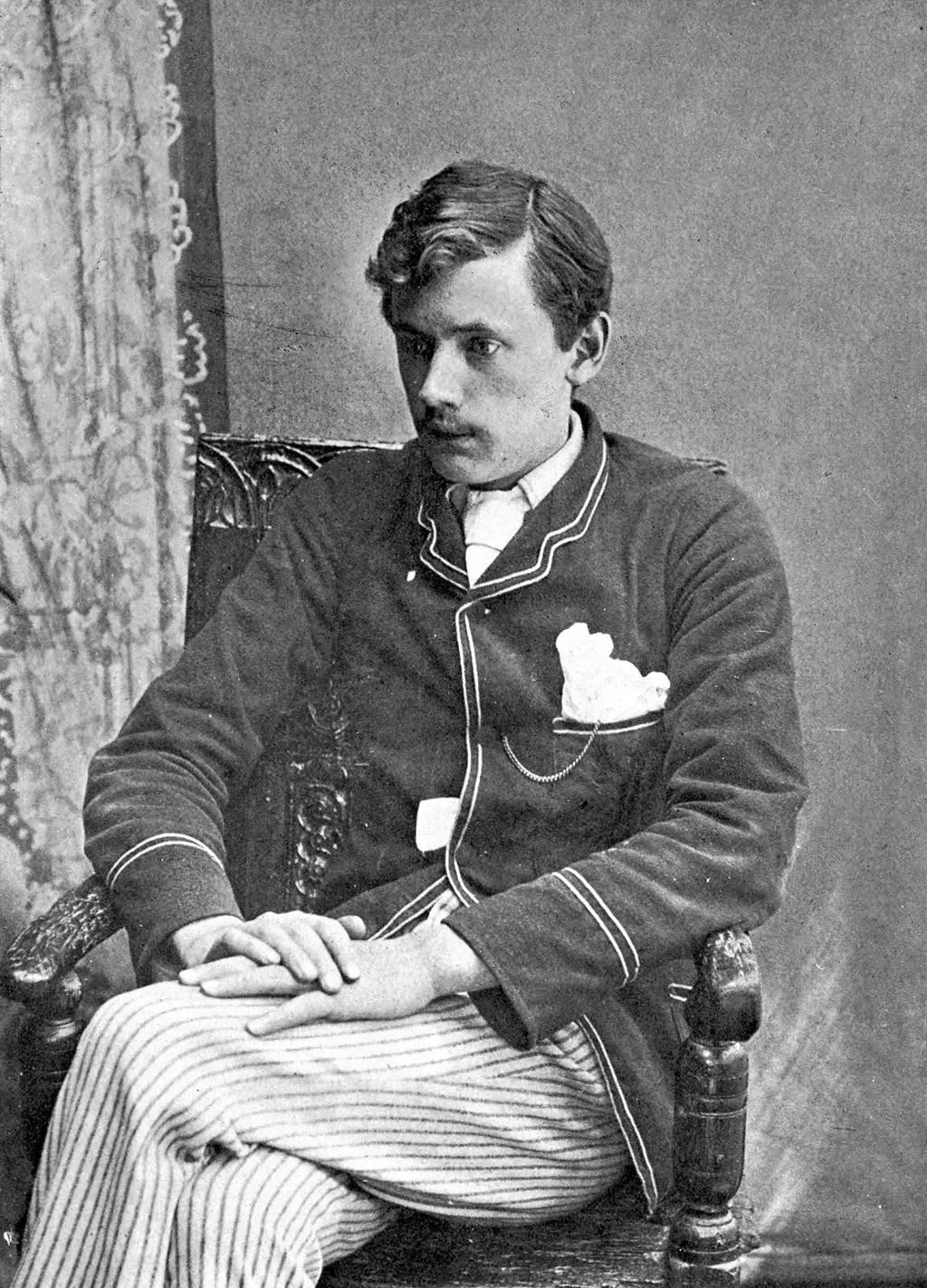

Ernest Dowson

Ernest Dowson, source: Wikipedia

English poet, novelist, and short story writer Ernest Dowson (1867-1900) was a regular at The Crown. Located in Charing Cross, The Crown was the decadent pub of the morally suffocating late Victorian Era and counted Oscar Wilde among its regulars. Dowson strongly believed that pubs were spaces of inspiration and wrote many verses there.

Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, source: ye-olde-cheshire-cheese.co.uk

Another pub that Dowson frequented was Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese. In the early 1890s, the pub was the headquarters of the Rhymers’ Club founded by William Butler Yeats and Ernest Rhys. Poets met at the Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, ate, drank quite a few tankards, smoked pipes, and recited verses to each other. And the drinking part was taken very seriously – so much so that at one point Dowson even formed a splinter group called the Bingers. And Yeats himself mentioned the pub in his 1914 poem, “Grey Rock”:

Poets with whom I learnt my trade,

Companions of the Cheshire Cheese…

Ian Fleming, the creator of James Bond, was a regular of the Dukes Hotel Bar. In fact, many believe that the inspiration for the famous line “shaken, not stirred” was Dukes’s bartender.

Charles Dickens

Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese was Charles Dickens’s (1812-1870) favorite pub as well. The prolific author had his own chair and table on the ground floor, right next to the fireplace. Such was his adoration of the Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese that Dickens included it in his A Tale of Two Cities as the pub where Darnay recovers after being acquitted.

Charles Dickens, source: Wikipedia

Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese features another literary work from the early 20th century. In Agatha Christie’s The Million Dollar Bond, Hercule Poirot – who is a difficult man to please by all accounts – dines with a client at the pub and praises the “excellent steak and kidney pudding.” The pub was indeed renowned for the hefty puddings they served.

Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese was not the only pub Dickens frequented. He was also a regular at the George Inn (located on Borough High Street, Southwark). The medieval public house was burnt down and rebuilt in 1677, and remains the only galleried coaching inn in the city. Dickens mentions the George Inn in both Our Mutual Friend and Little Dorrit.

George and the Vulture, source: georgeandvulture.com

However, the pub that plays the most prominent role in any of Dickens’s novels is The George and the Vulture. In Pickwick Papers, it is the regular meeting place of Mr. Pickwick and his friends, and people who want to locate the former often inquire at the pub first. The following passage reflects how much Dickens loved The George and the Vulture:

Joseph Clayton Clarke - Mr Pickwick, source: meisterdrucke.com.tr

“Mr. Pickwick and Sam took up their present abode in very good, old-fashioned, and comfortable quarters, to wit, the George and Vulture Tavern and Hotel, George Yard, Lombard Street. Mr. Pickwick had dined, finished his second pint of particular port, pulled his silk handkerchief over his head, put his feet on the fender, and thrown himself back in an easy-chair, when the entrance of Mr. Weller with his carpet-bag, aroused him from his tranquil meditation.”

The pub continues to host the meetings of City Pickwick Club since its foundation in 1909: “Members take the names of characters in the book; they enjoy ‘wanities’ (drinks), eat their ‘wittles’, hear speakers and toast ‘the Immortal Memory of Charles Dickens’.”

Further Reading

Charles Dickens. A Tale of Two Cities. London: Penguin. 1859.

Charles Dickens. The Pickwick Papers. London: Wordsworth. 1993.

Mehmed Kemal. Acılı Kuşak. İstanbul: De. 1977.

Meyhane İhtisas Kitabı. A’dan Z’ye Meyhane: Nedir, Nasıl Çalışır? Istanbul: Anason İşleri. 2022.

Orhan Veli. Hoşgör Köftecisi. İstanbul: Yapı Kredi. 2000.

Rakı Ansiklopedisi: 500 Yıldır Süren Muhabbetin Mirası. Istanbul: Overteam Yayınları. 2012.

Refik Durbaş. Rakı ile Edebiyat Muhabbeti. İstanbul: Heyamola. 2007.

Sadun Tanju. Eski Dostlar. İstanbul: İnkılap. 1996.

Salah Birsel. Ah Beyoğlu, Vah Beyoğlu. İstanbul: Sel. 2022.