Alembic – Where every drop counts

With its distinguishable cloudy white color, anise taste, and distinct aroma, rakı has been part and parcel of Istanbul’s culinary culture for centuries. Variants of rakı, made of twice-distilled grapes and flavored with aniseed, are enjoyed in countries all across the Mediterranean. However, as many an aficionado will waste no time reminding you, rakı is much more than a drink: it is an irrefutable feature of social and cultural life, a building block of local identity, a catalyst for socialization, a symbol of camaraderie, and so much more. And in our journey to the heart of this drink that is much more than a drink, we must first turn our attention to 9th- century Mesopotamia.

First came the alembic

The first references to alembic are seen in the 3rd- and 4th-century works by Cleopatra the Alchemist, Synesius, and Zosimos of Panopolis, who believes it was Mary the Jewess (who is considered by many to be the first true alchemist of the Western world) who invented the vessel.

Most rakı historians believe, however, that basic distillation technology was developed by Arab and Persian alchemists in Mesopotamia during the 9th century.

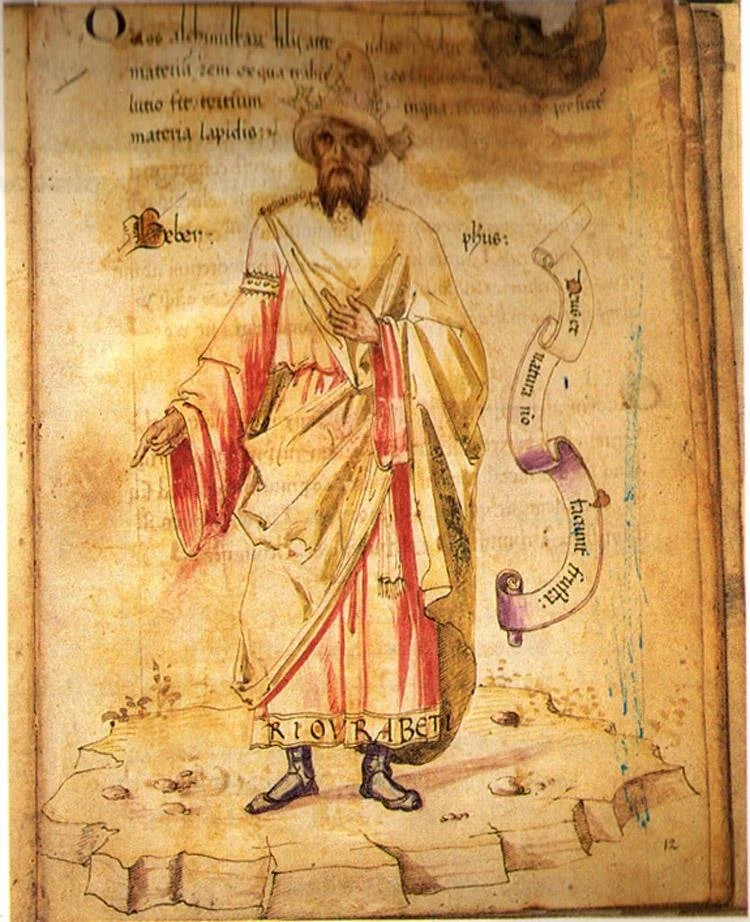

Drawing and description of Alembic by Jabir Ibn Hayyan, source: wikimedia

Depiction of “Geber” in a Latin alchemical manuscript of the 15th century, Ashb. 1166, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, Florence, source: wikipedia

Jabir bin Hayyan, also known as the “Hippocrates of Chemistry,” established the world’s first chemistry laboratory, which included a still. Amongst his followers were the Arab polymath Al-Kindi and Persian scholar Al-Razi, who developed a theory of distillation, which led to the birth of the ancestor of all distilled drinks: arak.

Al-Kindi, source: totallyhistory.com

According to Erdir Zat Al-Kindi’s Book of the Chemistry of Perfume and Distillations is considered to be one of the oldest references for distilled alcoholic beverages. However, as Robert James Forbes notes, the oldest known work focusing on the production of distilled beverages was written by Magister Selarnus (from the Sculoa Medica Salernitana, the first medical school founded in medieval Italy), who provided the first recipe for the fractional distillation of alcohol.

From arak to rakı

Arak, Muaddi

Arak means “sweat drop” in Arabic, and the drink is thought to have been named so, as the drop of distilled alcohol at the cap of the alembic resembled a sweat drop. We do not know for certain when this translucent and unsweetened Levantine spirit of the anise drinks family and hence, for many, rakı’s primogenitor was first produced. However, many historians of arak believe one of the first references to the beverage was made in historical documents dating back to 1326 when Ottoman Sultan Orhan Bey sent dervish Geyikli Baba and his followers two crates of arak in appreciation of their help in conquering Prusa (Bursa), a city located southwest of Constantinople.

Fuzûlî, source: wikimedia

References to arak and rakı multiply after the 16th century. Poet Fuzuli mentions rakı in his Beng ü Bâde (Hashish and Wine) thought to have been written sometime between 1510 and 1514. The narrator of the anonymous Viaje de Turquie (The Turkish Journey) claims he drank his first rakı (rendered raqui) on the island of Limnos and according to the famous Ottoman traveler Evliya Çelebi, among the most popular arak types in 17th-century Constantinople were: aniseed, sweet, cinnamon, mustard, date, clove, linden, and Persian. Antoine Galland, the French orientalist who visited Smyrna in 1678 mentions that arak was drunk in all the meyhanes across the city and his compatriot, botanist Joseph Bitton de Tournefort describes how rakı was produced in various parts of Anatolia at the start of the 18th century.

However, it was only at the beginning of the 19th century that the first popular kind of rakı emerged in Istanbul: mastika.

Seasoned with aniseed and mastic – a resin with a slightly cedar-like flavor gathered from the mastic tree native to the island of Chios, and hence called the “tears of Chios” – mastika’s popularity gradually increased throughout the first half of the 19th century. Mastika was dethroned in the 1880s however, by its sister düziko. Düziko came from the word düz, meaning plain or straight; in the rakı lexicon, it described the kind of rakı that was flavored only with aniseed and which is the classical rakı sold in Turkey today. According to Ahmet Rasim, during the early 1880s düziko replaced the traditional mastika with astonishing haste and ubiquity. As historian François Georgeon claimed, this was a pervasive shift – Istanbulites from all socio-economic strata, from the porters to artisans, from sailors to journalists, from the bottom of the ladder to the top, gave up the mastika in favor of the düziko.

Elif Duziko, source: buyukkeyif.com

Following the privatization of the industry in 2004, a wide range of rakı types, all required to use Pimpinella anise and grapes produced in Turkey, appeared in the market: classical (made with raisins or grapes and contains up to 35% ethyl alcohol); fresh grapes (only uses fresh grapes and does not contain any ethyl alcohol); triple distilled; oak barreled; sugar-free; organic; craft (produced in small scale and different flavors are experimented); mono-varietal (using only one type of grape).

Distillation

The process starts with fermentation. Although figs are used in some parts of southern Anatolia, grapes are rakı producers’ favorite for three reasons. First, their sugar levels are relatively high: 18 in every 100 grams. Second, they are faster to produce and process, which makes them economically viable. And third, their aroma blends nicely with that of anise. Fermentation starts when yeast is added to grape juice and the mash obtained has around 10-15% alcohol.

Steps in making Rakı, photograph by Halil Kayır, source: Rakı The Spirit of Turkey by Erdir Zat

Fermentation is followed by a two-stage distillation process. First, the mash is distilled in modern alembics. During this process, the alcohol strength is increased, and unwanted by-products of fermentation (such as sulfur) by evaporation and then condensation of the mash. The suma obtained at the end of this stage has up to 94.5% alcohol. In the second stage, this suma is distilled with anise seeds and rakı is produced. However, the alcoholic content of the distillate is too high to be suitable for consumption at the moment. So, demineralized water (which has no impact on the flavor or aroma) is added to the distillate to reduce the alcohol level to 40-50%. Finally, rakı is rested in oak barrels or steel tanks for about a month whereby the flavor gains consistency, the taste smoothens, and the raw rakı smell fades away.

Steps in making Rakı, photograph by Halil Kayır, source: Rakı The Spirit of Turkey by Erdir Zat

For two reasons, most rakı producers prefer to use copper alembics in the distillation process. First, copper is a good conductor of heat as it absorbs heat quickly and holds it for a long time. Second, as the liquid vaporizes it comes into contact with the copper surface of the still, and this interaction produces chemical reactions that enhance the aroma and flavor of the distilled spirit.

Savoring rakı

Although the way people enjoy rakı has evolved through centuries – a topic we will be delving into in a few weeks – today, the lion’s milk is very often consumed by adding some water and one or two cubes of ice to it. A word of caution: Adding ice before the water crystallizes rakı and spoils its flavor and smooth complexion.

Pop-up Meyhane, Istanbul's Armenian Mezes by Istanbul Elsewhere, London, photo by Ferhat Elik

One aspect of rakı culture that has not changed since rakı made its way to meyhanes in Constantinople in the 17th century is its special relationship to mezzes. Indeed, what we call a rakı table feels and truly is incomplete without mezes, which offer not merely culinary but often also visual delights. But it is important to note that mezzes are not there to fill up on but enjoy in small amounts. As the doyen Istanbulite Vefa Zat once said: “It is unbecoming to attack the mezzes. They are not there to be gorged on but to be tasted. Eat slowly and in tiny amounts. After all, what truly matters with the mezze is sharing it with your loved ones.”

Rakı Ansiklopedisi, source: Anason İşleri

Aside from these physical accompaniments, like every other cultural institution, rakı has its own unwritten code of conduct; an ethos that grounds, surrounds, and sustains it. These rules, for lack of a better phrase, have amassed over decades, as people’s comportment towards one another and themselves while savoring rakı has evolved. Rakı Encyclopedia provides a summary of some of the rules that have survived the sands of time: showing respect to your companions; listening without interrupting; never using words that could hurt your fellow drinkers ; not causing disturbance to people around you; avoiding improper overtures; and of course, drinking responsibly and handling your drink – “to remain tipsy for as long as possible without getting drunk.”

Açık Hava Meyhanesi by Istanbul Elsewhere, London photo by Ferhat Elik

Perhaps, though, the most important feature of this ethos is sharing: sharing not only the rakı and mezzes but also your joys, troubles, laughter, tears, memories, hopes, disappointments, and fears; baring yourself and allowing others to do the same. This is how rakı creates a camaraderie that turns it into something more than a drink.

Further Reading

Ahmet Rasim. İstanbul’da Eğlence Hayatı. Istanbul: Maviçatı. 2017.

Erdir Zat. Rakı: The Spirit of Turkey. Istanbul: Overteam Publishing. 2012

François Georgeon. Rakının Ülkesinde: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu’ndan Erdoğan Türkiye’sine Şarap ve Alkol (14. – 21. Yüzyıllar). Istanbul: İletişim. 2023.

Rakı Ansiklopedisi: 500 Yıldır Süren Muhabbetin Mirası. Istanbul: Overteam Yayınları.

Robert James Forbes. A Short History of the Art of Distillation: From the Beginnings up to the Death of Cellier Blumenthal. Leiden: BRILL. 1970