It’s All About the Anise

Pimpinella Anise, source: Mey | Diago archives

What gives rakı its unmistakable aroma, smooth taste, and cloudy white color is anise. Not just any anise though; Pimpinella anisum, a flowering plant in the family Apiacea (commonly known as the celery, carrot, or parsley family, or as umbellifers) and also known as green anise or simply as anise, is the only kind used in rakı distillation.

Pimpinella, source: Wikimedia

Star anise, a fruit harvested from the Asian evergreen trees (illicium verum) is a different species. However, some Mediterranean anise-flavored alcohol producers have recently started using the Southeast Asian spice as it is considerably cheaper to produce.

A Mediterranean tradition

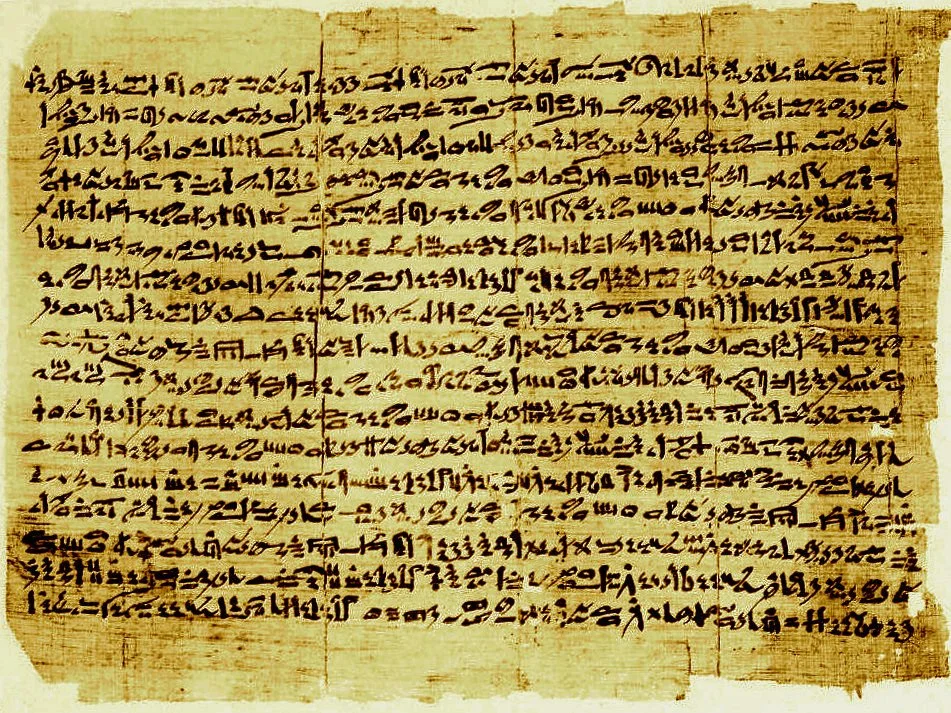

Anise is thought to have been first cultivated in ancient Egypt sometime in the 2nd century BCE. The Hearst Papyrus (one of the medical papyri of ancient Egypt dated circa 1450 BCE) mentions not only its health benefits but also that it was frequently used alongside cumin to add flavor to dishes. Likewise, many an antiquarian medical figure, including Hippocrates, praised anise’s distinct and sharp aroma, aphrodisiac effect, and healing power for digestive problems. Today, anise continues to have a pivotal role in Mediterranean culture and is used in alcoholic beverages, bakery items, meat and vegetable dishes, and herbal teas.

Papyrus Hearst Plate, source: Wikimedia

According to cultural historian Ahmet Uhri, it is the sharpness of its odor that makes anise a prime aromatizing agent for alcoholic beverages and bakery items since the Medieval Times. One of the earliest recorded examples of the use of anise in alcoholic beverages was the onios anisatos, anise- and honey-flavored wine produced in the Byzantium Empire.

Rakı’s extended family

Before we embark on our journey through other anise-flavored drinks of the Mediterranean (and Americas), two points of clarification are in order.

Anise seeds, source: britannica.com

First, there are two different ways anise can be used in the production of alcoholic beverages. Anise or its extract can, like other spices such as star anise, fennel, licorice root, or Angelina, be macerated in alcohol.

This simple and cheaper aromatisation method drastically differs from how rakı and a few other relatives are produced: namely, by distilling alcohol together with aniseeds (and in some cases, other herbs and spices) thereby creating the unique, rich flavor.

The second point regards the ratio of ethyl alcohol of agricultural origin used in the distillation process. Turkish law limits this ratio to 35% and many contemporary kinds (such as the fresh grape rakı) use only alcohol obtained from the fermentation of fresh grapes. Although there are a few other distillers that prefer this method, many opt to use quite higher amounts of ethyl alcohol of agricultural origin as it reduces their distillation costs drastically.

Tutone Sicilian Anise, source: siciliabeddashop.com

According to historian Uhri, when Arabs conquered Sicily in the 9th century they took their stills, that is alembics, with them. Unlike Arabia, the island was a fertile ground for grapes, whose juice they distilled to use as an accelerant in lamps. Because their religion banned it, they did not consume alcohol. However, Sicilans, watching their conquerors, had an idea; they followed the distillation method to a T and added anise to the obtained distillate, creating a beverage they called Tutone. Tutone, which some see as one of rakı’s ancestors, is still produced to date using wine spirit, caraway, and star anise seeds but the recipe for distillation dating back to 1813 and written on a small and jealously guarded piece of paper, remains a secret.

Arak

Arak means “sweat drop” in Arabic, and the drink is thought to have been named so, as the drop of distilled alcohol at the cap of the alembic resembled a sweat drop. However, as Rob DeSalle and Ian Tattersall point out in Distilled: A Natural History of Spirits, “with a variety of derivatives, the term arak might be the most ancient of the names currently used for all kinds of distilled spirits.” (Indeed, in Japan, as far back as the 16th century, all strong distilled liquors were called araki.)

Distilled A Natural History of Spirits by Rob DeSalle and Ian Tattersall, Illustrated by Patricia J. Wynne, source: Yale University Press

In the Levant, distillers are free to choose their production methods. Some opt for the easier and cheaper way and use ethyl alcohol of agricultural origin and/or simply add anise as flavor. Others such as the Lebanese El Massaya keep the centuries-old tradition of distilling alive and prefer the time-consuming, complicated methods that enhance palatability, rewarding the distillers for their patience and loyalty.

Massaya Arak, source: massaya.com

Taking their cue from the Lebanese saying, “The better the wine, the better the arak,” El Massaya only uses Obeïdi grapes from the Beqaa Valley. Hand-harvested in September, the grapes are first fermented into wine (13% alcohol). Then, wine is distilled in Moorish-lid stills into brouilli (low-grade alcohol at about 45%). Next, the broulli is distilled in Moorish-lid stills into the second chauffe (medium-grade alcohol at about 65%). Finally comes the key stage of distillation where the second chauffe is macerated with green aniseed grown in Hiné and distilled for the third time (low-grade arak at about 70%).

The low-arak is then transferred to amphorae, where it turns into high-grade arak as the angel’s share – the low-density alcohol that prevents arak from being smooth and silky – evaporates. The rested, matured arak is diluted to 50% before sale.

Muaddi Arak

Another arak producer that uses only alcohol produced by fermenting wine and uses traditional distillation methods is the Palestinian Muaddi. As a boutique, craft distillery, Muaddi uses grapes from western Bethlehem and northern Hebron; aniseed from Raba; and clay amphorae hand-made in Hebron. The triple-distilled artisanal arak, whose first patch was produced only in 2017, has already won numerous gold prizes in international spirits competitions.

Tsipouro

Rumored to have been first produced by Greek Orthodox monks on Mount Athos in the 14th century, tsipouro is made from grape pomace – skins and stems left after the grapes are pressed for wine. Like rakı, it is twice-distilled (with anise added to the distillate during the latter). No ethyl alcohol of agricultural origin is used in the making of tsipouro, which also comes with a plain, non-anise flavor. The anise-flavored version is mostly preferred in the northern parts of the country and is enjoyed alongside an array of mezes either in a shot glass or broad tulip glass which helps expand its aroma.

Double-Distilled, Anise, Flavored Tsipouro, source: biologikoxorio.gr

Ouzo

Frequently confused with rakı by novices, ouzo occupies an invaluable place in Greek culture. There are a few conflicting accounts regarding where the name ouzo comes from. Some literary scholars believe it comes from the ancient Greek verb “to smell,” or “ozo.” Those of a more romantic conviction think it comes from “ou zo,” meaning “without which I cannot live.” Others see its roots in the Turkish word for grape, “üzüm.” And finally, some claim it originated in the early 19th century in Tryvanos, a silk-producing town in northeastern Greece. Those who enjoyed the drink were adamant that its smoothness could only be rivaled by “uso di Marsiglia,” the name used for premier silk bound for Marseilles ports.

Ouzo, source: discoverrhodes.com

There are two major differences between the production of ouzo and rakı. Although aniseeds are distilled with alcohol, these are not the only spices used in ouzo’s making: Cardamom, fennel, mastic, coriander, ginger, and cloves are also widely included. Second, almost all ouzo producers only use ethyl alcohol of agricultural origin. In other words, no fermentation is involved in the process and the final product ends up sweeter and lighter than rakı.

Absinthe

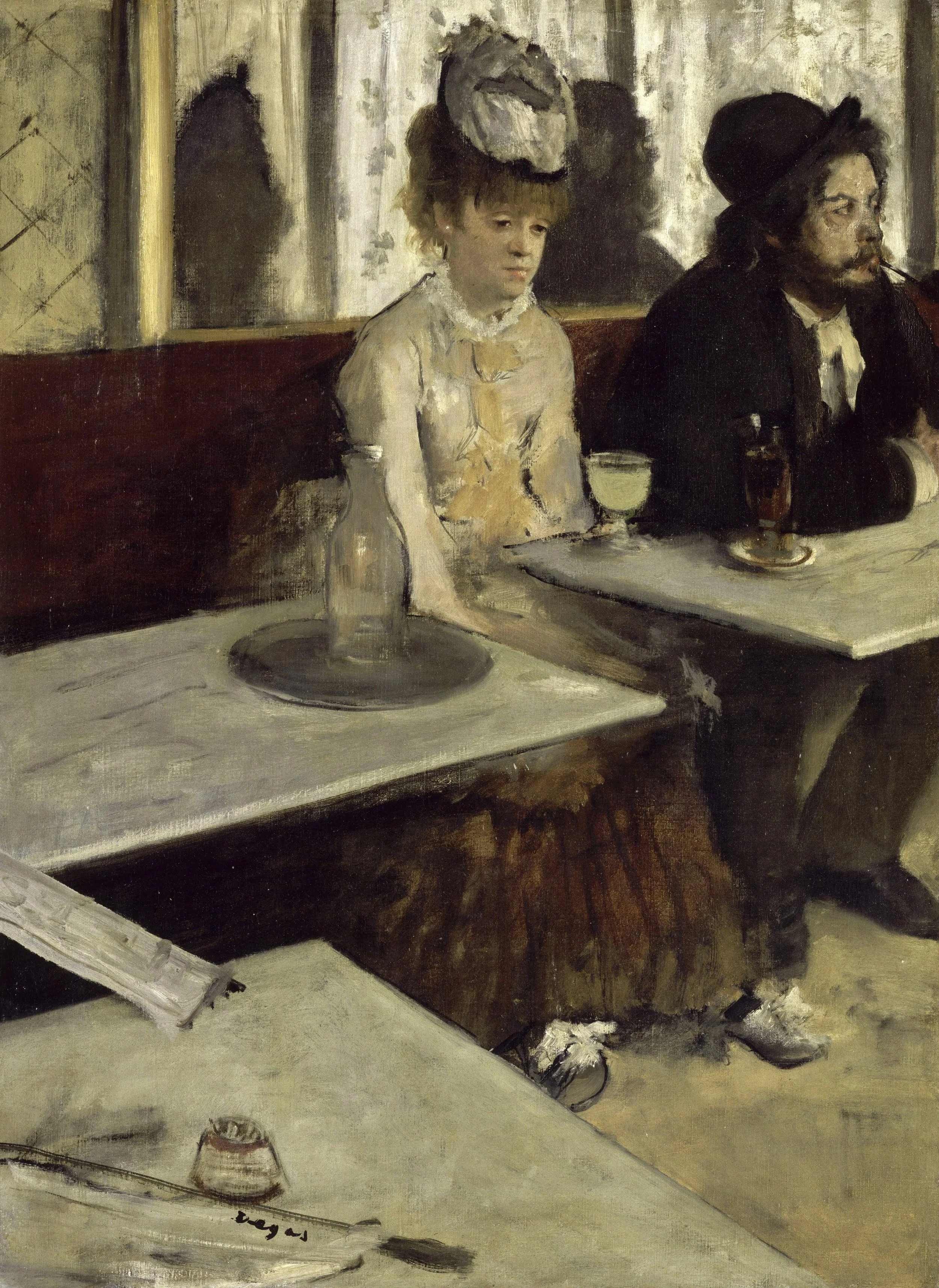

Arguably the most infamous of all aniseed-flavored drinks, absinthe was created in Neuchâtel, Switzerland in the late 18th century by the French doctor Pierre Ordinaire. It has often been portrayed as a dangerously addictive hallucinogen and associated with crimes and disorder. There was also the popular view that absinthe addicts were sodden and benumbed, as epitomized in Edgar Degas’s 1876 painting L’abstinthe.

Dans un café, dit aussi l'Absinthe, In a cafe by Edgar Degas, source: Wikimedia

By 1915, absinthe was banned in the US and much of Europe including France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, and Austria-Hungary. However, modern studies have proven that absinthe is not any more dangerous than ordinary spirits and that its psychoactive properties have been exaggerated. As a result, la fée verte (“the green fairy” is the literary name assigned to absinthe as it was traditionally of that color but colorless versions also exist) went through a revival in the 1990s and today nearly 200 companies produce absinthe in Europe alone.

Absinthe gained immense popularity in Bohemian circles during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Some well-known names who could not resist the temptation included Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Lewis Carroll, Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, Arthur Rimbaud, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. In fact, so popular was the drink by fin de siècle that in bars, cafes, and cabarets, 5 p.m. was called l’heure verte (green hour).

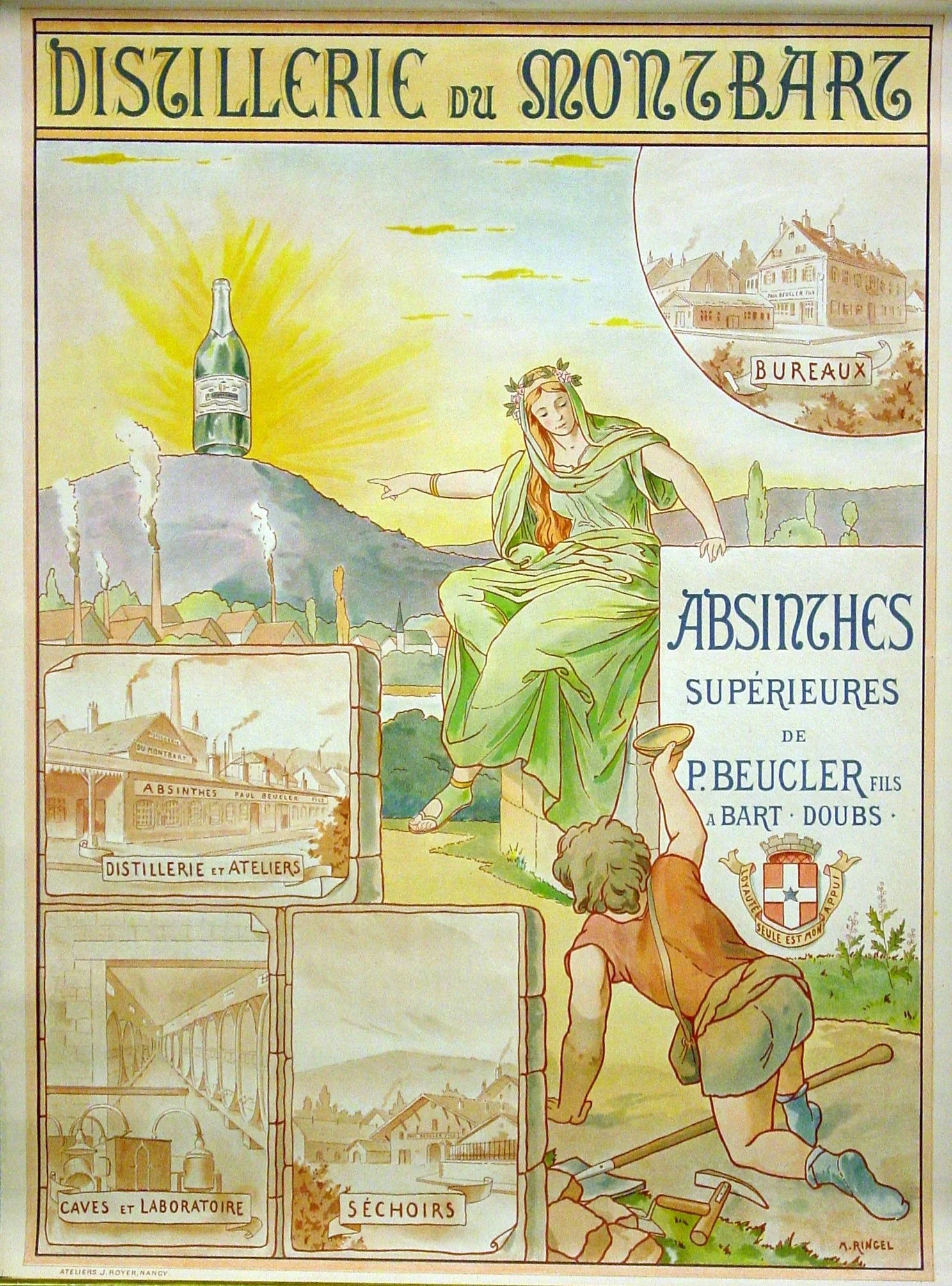

Absinthe, Paul Beucler Collection personnelle photo arnold.p ; oct 2007, source: Wikimedia

Because most countries do not have a legal definition for absinthe, producers are at liberty to follow any production method available. However, most legitimate producers follow one of two historical processes: distillation and cold-mixing. (Switzerland, the sole country with a legal definition of absinthe, only allows distillation.) In distillation, herbs, including the “holy trinity” of grand wormwood, anise, and sweet fennel, and others are distilled with alcohol. Although traditionally white grapes were fermented to create the base, today almost all companies entirely use ethyl alcohol of agricultural origin.

Pastis

Pastis became very popular in France after absinthe was banned likely because people had already developed a penchant for anise-flavored drinks. Star anise and licorice extracts are used in the making of pastis, and herbs are not distilled with alcohol but mixed afterward. Like many other anise-flavored drinks, it is diluted with water before drinking whereby its color turns from dark transparent yellow to milky soft yellow.

In Marseilles, where the drink enjoys immense popularity, pastis is seen as a staple of Provençal lifestyle (just like pétanque) and nicknamed pastaga.

Pastis, source: culinarybackstreets.com

Chinchón

Named after the Madrid village it is made in, chinchón is a distilled beverage that only uses green anise (that is, the Pimpinella). Its origins go back to the 17th century, when the marc, left over from winemaking was distilled together with the aniseed. Today, the production process comprises two phases. First, aniseed is macerated in an alcoholic solution of moderate strength. Then aniseed is distilled in copper stills with only ethyl alcohol of agricultural origin.

Sambuca

According to some historians, the name sambuca derives from an Arabic word, zammu, which was the name of an anise-flavored non-alcoholic drink that arrived at the port of Civitavecchia by ships arriving from the East. The alcohol-infused version was called zambur and in Italian, the word changed to sambuca.

The distillation process of sambuca is very similar to that of rakı however, crucially only star anise and ethyl alcohol of agricultural origin are used.

Sambuca and coffee beans, source: thespruceeats.com

Con la mosca is the traditional way of serving sambuca. The drink is served neat with three coffee beans symbolizing health, prosperity, and joy.

Aguardiente

Aguardiente is a compound of Iberian language words for water (agua) and burning (ardent). In Colombia, it is produced by first fermenting sugar cane, and then star anise is added during the distillation process. By law, the end product has to be diluted until its ABV drops to between 24 and 29%.

Anisette

Anisette was introduced in France by distiller Marie Brizzard in 1755. She allegedly had obtained the recipe from a West Indian man whom she nursed through a life-threatening illness.

Traditional anisette is distilled with aniseed, like rakı, and is differentiated from those produced by simple maceration by including the word distilled on the label. Other herbs, especially licorice roots, are also used in the production process of this sweetest-tasting anise-flavored drink. Almost all anisette producers rely on ethyl alcohol of agricultural origin.

Marie Brizard Anisette, source: lespetitscelliers.com

Further Reading

Meyhane İhtisas Kitabı. A’dan Z’ye Meyhane: Nedir, Nasıl Çalışır? Istanbul: Anason İşleri. 2022.

Rakı Ansiklopedisi: 500 Yıldır Süren Muhabbetin Mirası. Istanbul: Overteam Yayınları. 2012.

Rob DeSalle & Ian Tattersall. Distilled: A Natural History of Spirits. New Haven: Yale University Press. 2022.

Scott C. Martin (ed.) The SAGE Encyclopedia of Alcohol: Social, Cultural, and Historical Perspectives. New York: Sage. 2015.